"You picked the service of your choice, there wasn't much else you could do. I didn't really want to drown, so I stayed out of the navy; I didn't want to be shot, so I stayed out of the infantry..."

Although it wasn't a simple a matter of choosing your favourite armed service, Harrison managed to end up in the US Army Air Corps two months after he graduated. He achieved that by attending Eastern Aircraft Instrument School in New Jersey, where he became a certified aircraft instrument mechanic.

"Before I was drafted I went to an aircraft instrument school to learn to repair aircraft instruments. I wanted to get into the airforce, I'd always liked 'planes. Of course I never saw an aircraft instrument again! But I had good mechanical aptitude - in fact the best mark I ever had in my life, which meant I ended up at the technical school."

The Air Corps sent him to Lowry Field in Denver, Colorado, where he was trained to be a power-operated and computing-gunsight specialist. He learned computer theory and how to repair the computer itself: it was a mechanical computer, and work on the tiny rods and cogs had to be carried out under clean-room conditions.

In 1944 Harrison was sent to the Air Corps base in Laredo, Texas, where he was to maintain the computer which controlled the aim of two fifty-calibre machine guns which were mounted on turrets on a truck, which gunners were trained to use. His duties soon came to include that of armourer, truck driver, and then gunnery instructor - "teaching kids to shoot machine guns", as the holder of each of these posts was called away to combat duty.

In 1945 he was transferred to a gunnery school in Panama City, Florida, which was soon to close down. He was then assigned to M.P. duty and promoted to sergeant. His job now was to ride shotgun on a garbage truck, guarding the black prisoners who worked it. Despite the fact that he was armed with a loaded repeating shotgun, his charges didn't really need much supervision. They had been punished for some misdemeanour, and now wanted to serve their time on best behaviour and gain an honorary discharge, as the war was coming to an end. Harrison knew how the prisoners felt: he used to drink with them in the black servicemen's bar.

Sergeant Harry Harrison was discharged on 14th February 1946.

"The war did many good things for me, though I certainly did not appreciate them at the time. First, and most important, it kicked into existence a strong sense of survival that has been of great service since. It also terminated my childhood, a fact that I was certainly not grateful for at the time since growing up can be a painful process. I also learned to drink and curse, the universal coin of military life, but, more important, I was robbed of three years of my life without satisfactory return. At least I believed so for a long time, which is the same thing, and this gave me that singular capacity for solitary work, the drive to get it done, without which the freelance cannot survive."

The army had also given him a knowledge of, and interest in, computers, a subject which continues to interest him today: the Harrison household is filled with computers, from 'toy computers' which Harrison has used to help develop the computer games based on his novels, to the latest and most powerful lap-top computer.

"Coming out of the army was a traumatic experience and years passed before I could understand why. It seems very obvious now... Though I loathed the army I was completely adjusted to it. I could not return to the only role I knew in civilian life, that of being a child."

After training as a commercial artist, working in magazine and comic book illustration, and then editing and packaging magazines, Harrison turned to writing. He wrote in a genre which he had loved since his childhood, and sold several science fiction short stories. Under the guidance of editor John W.Campbell, he wrote his first full-length novel, Deathworld, which was first serialised in Campbell's magazine.

"I did Deathworld about seven or eight times in various ways," Harrison admitted to Charles Platt in 1982. "Once I got the formula right, I disguised it with different kinds of titles. Deathworld had worked. I knew I could make money off that formula."

"The world was quite happy with my work; I wasn't... I wanted to write better and I wanted to write different material," Harrison revealed in Hell's Cartographers. "Salvation came through the good offices of Joseph Heller and Brian Aldiss. I read Catch- 22 which crystallised my thinking, and I had met Brian Aldiss a few years earlier. In addition to his friendship, which I value above all others, I appreciate his literary and critical skills. Brian is a prose stylist, and certainly the best in science fiction... It was a little late, but my literary education had begun."

Harrison had written several experimental short stories previously: 'Captain Honario Harpplayer, R.N.,' was a parody of the Hornblower tales of C.S. Forester, which Harrison enjoyed in his youth; 'The Streets of Ashkelon' tackled the then taboo subject of religion; and even the original Stainless Steel Rat short stories were a gamble because "you couldn't sell humour unless you were an accepted humour writer... I had to disguise them as adventure stories and slip in any lightness and humour."

"All of my experimentation so far had been in the short story, since the time investment there is obviously much less than the novel. This was both good and bad because the 'experimental' did not do very well, not in these dark days of the early sixties. The quotes are around experimental there because my stories were nothing of the kind. They just fell outside the classic pulp taboos that still dominated the field."

Harrison admits to being "hesitant to put the time into an entire novel that might not sell. At that period a novel a year was the most I could do and the thought of losing a year's income was not to be considered."

"Eventually the artist triumphed over the businessman, ears became numb to the sound of hungry children crying in the background, and I contacted Damon Knight. Damon was acting as an sf literary scout for Berkley Books and I was sure he would be simpatico to my needs. I sent him the first (and only) chapter I had written of an experimental novel titled If You Can Read This You Are Too Damned Close. With it were some one page character sketches and a few words about the kind of novel I wanted to attempt."

Damon Knight liked what he saw, and persuaded Berkley to give Harrison a $1,500 advance, $750 on signing, with $750 to come when the book was completed. Harrison went to work.

"I wanted to get my feelings about the army and the military into a novel," Harrison wrote in his notes for authors of the new series of BILL books. He explained that the original book was founded on "a deep-seated suspicion of the military, and a profound hatred of war and the people who like and want war."

Harrison cites Heller and Voltaire as inspirations for BILL: "I got the clues I needed from Candide and Catch-22: do it as black comedy. Some things are so awful they can only be faced by bitter laughter. To this I added parody of other sf." [From the notes for the authors of Bill sequels.]

Two of the sf writers parodied in BILL are Isaac Asimov, whose metal-plated planet Trantor from the FOUNDATION series appears as the gold-plated planet Helior (which turns out to be anodised aluminium in reality), and Robert Heinlein, whose controversial Starship Troopers is openly attacked. Starship Troopers is, according to Aldiss' Trillion Year Spree, "a sentimental view of what it is like to train and fight as an infantry man in a future war." While Brian Ash's The Visual Encyclopedia of SF said of it: "It was the presentation of an extreme elitist society, coupled with the glorification of violence, which made the book distasteful to many readers."

Isaac Asimov, it is said, took Harrison's parody in good humour, and might even have been pleased to be parodied. Robert Heinlein, apparently was not pleased.

In his book Robert Heinlein, Leon Stover describes Bill as a "dramatic summary" of all the criticisms levelled against Heinlein's Starship Troopers. "Hailed by critics as a work of comic genius, it divided Harrison's fellow writers and troubled his fans; both of whom reserved the right to award him his due for later works equally brilliant, but less nervy in touching upon Heinlein's good name. The critics, however, continue to favour this one Harrison title above all, simply because they read it as a digest of everything they despise in Starship Troopers."

Ash's book describes Bill, the Galactic Hero as "a savagely funny satire which tilts at several sacred cows of sf warfare, as well as religion. It contrives to satirise the clichés of interstellar war and space opera... The public are told that the alien race with which man is waging an all-out war are seven-feet-tall intelligent lizards of hideous appearance - they actually turn out to be only seven inches long. The cruel military training of new recruits is precisely documented, on a par with Heinlein's book, but Harrison's interpretation of military ideology is the very opposite of that in Starship Troopers. The grotesque violence of Bill, while presented as farce, is revealed as a crime against humanity, or any other species, and unjustifiable under any circumstances."

The writing of Bill was a "shaking experience" for the author. "I was doing less than half my normal wordage everyday and greatly enjoying myself - at the time. Laughter all day at the typewriter - how I do enjoy my own jokes - instant depression when I came down for dinner. Upon rereading, the stuff seemed awful. Or awfully way out; there had never been anything like it in SF before. Then back the next day for some more chuckling and suffering."

Harrison was encouraged by his wife, Joan, who was "reading the copy and laughing out loud and saying it was great and get on with it and stop muttering to yourself. I got on with it, finished it, had it typed and mailed it off to Damon."

Damon Knight rejected the novel. The reason he gave was that "what I had here was an adventure story loused up with bad jokes. Take the jokes out and it would be okay."

Berkley's editor-in-chief, Tom Dardis, liked the novel as it was, but didn't want to appear to contradict his paid sf advisor. Fortunately Doubleday sf editor Tim Seldes picked up the US hardback rights, encouraging Berkley to take it in paperback. Frederik Pohl published a shortened version of the novel in Galaxy, under the title The Starsloggers, and Michael Moorcock published the whole novel in three parts in New Worlds in the UK.

"Here was a message of some kind. SF was growing and contained within its once pulp boundaries new and different markets. Bill was positively not an Analog serial and had not even been submitted there. (In later years I discovered that my judgement had been correct in this at least. One day John Campbell asked me why I had written this book. I said I would tell him if he told me why he had asked. His answer was that he had seen my name on the paperback and bought it - as if he did not have enough sf to read! - and had hated it. I made some sort of waffling answer and worked hard to change the subject.)"

Harrison was encouraged by the success of Bill, the Galactic Hero: "I felt that there must be a bigger market out there than I had imagined and perhaps I could now write for myself and please the readers at the same time. This was a momentous discovery and marked a new period in my writing. Not that I didn't do the familiar to stay alive. Deathworld 3 and a number of Stainless Steel Rat books were still in the future, but I found I could experiment with new ideas and still hope to sell them as well."

Harrison has continued to alternate between the familiar - with a series of Stainless Steel Rat books; Invasion: Earth; and more recently a series of BILL sequels - and the more experimental / serious - A Transatlantic Tunnel, Hurrah!; Make Room! Make Room!; and the West of Eden and Stars & Stripes trilogies.

Bill, the Galactic Hero, meanwhile, has been read on BBC Radio (and the reading released on LP and cassette) and adapted into a series of comic books. A series of 'shared world' or 'share crop' sequels have also been produced.

© Paul Tomlinson 1995 & 1999

Interview with HARRY HARRISON

by Paul Tomlinson

PT: Bill, the Galactic Hero was first published in 1965...HH: It was one of the first things I wrote when I moved to Denmark, so I started writing it in 1961 or '62.

PT: At that time you were a 'Campbell writer' - you were doing pretty well in Astounding / Analog magazine...

HH: I sold the same book five times! Three Deathworlds, and then under two other titles!

PT: The readers were voting yours the best story, and you were getting paid the bonus...

HH: An extra penny, yeah. You were paid three cents a word, and the bonus was a penny a word extra. That doesn't sound like much today, but it was a third more. That's $600 on a 60,000 word serial. I got that penny every time.

PT: So why did you decide to throw away that security and go off and write something totally different?

HH: I didn't throw the security away... There were no paperbacks in those days, so if I wrote a book it had to be a serial for John Campbell. I was doing one a year on average. Then, when they did start publishing paperbacks, I had these books already written which I could flog as paperbacks. So for the first time in my life I had some money.

It had taken me a while to learn to be a novelist, but now things were going well, and I'd had this book in the back of my head for years that I'd wanted to write, about the war and my experiences and how I felt about the military.

I was writing Flash Gordon comic strips at this time, which just about paid for the food, but not the rent. And I was doing a lot of short stories - if you look at the list for that period, I'd do a novel and some short stories each year.

So I figured I'd try it as an original paperback. I knew John wouldn't even look at it! So I wrote to Damon Knight - who had published my first short story, and was an old friend - and sent him an outline for a book called If You Can Read This, You're Too Damned Close! and I did some character sketches. Damon was reading for Berkley Books then, and he got me a contract for $1,500 - big money! - $750 of it in advance. So I took a deep breath and wrote the book.

I never planned to show it to Campbell. But John did actually read the thing. He asked me: Why did you write this book, Harry? And I said: I'll tell you if you tell me how you knew about it. He said he saw it on a stand in the subway and bought it! As if he didn't read enough at work!

PT: The thought of John Campbell going out and buying a science fiction novel is something I can't quite...

HH: Neither can I! But I was 'his' writer, he'd done at least three, maybe four, of my novels as serials, and he saw this book that he'd never seen before.

PT: He hated it, presumably?

HH: Every word of it, I'm sure, or the idea behind it at least. He didn't have much of a sense of humour. He didn't publish much funny stuff if you think about it, or if he did it was pretty heavy-handed, like Poul Anderson's A Bicycle Built for Brew - good old engineering jokes, ho-ho-ho. Or a pirate coming out of a spaceship with a slide rule between his teeth! So he had a sense of humour, but he wouldn't go for black comedy or satire.

I don't think he got the point of the damn thing at all, but I didn't ask him in detail why he didn't like it when he said: I hated it. There are things you don't do!

PT: There are some things you don't want to hear from someone like John Campbell...

HH: Exactly. I was reading his magazine when I was 13 or 14 years old. He invented modern science fiction, his writers were writing really good stuff. He got rid of all the old hacks, hired a new generation of writers and shook up the whole field.

I grew up reading that stuff, carried on even when I came out of the army in '46 and went to arts school. Astounding came out on the third Thursday of the month, but one guy on the subway station down town used to break the bundles a day early, so I used to take the subway - twenty minutes down there, twenty minutes back - to get it the day before!

So when I started writing, it was my greatest pleasure to work with the guy who I read as a kid.

PT: In Bill, the Galactic Hero you made fun of some of the authors you read: you had a slight dig at Isaac Asimov...

HH: Oh, yeah! For Trantor read Helior. What do you do with the carbon dioxide? What do you do with the garbage? I had a dig at Starship Troopers too.

PT: That was a more direct attack, wasn't it? And Heinlein didn't take it too well?

HH: All I can say is, I asked Bob once if he'd read the book Bill, the Galactic Hero, and he said: No, I don't read most of the stuff other people write. But after that, he never spoke to me again!

PT: So maybe he went away and read it after you asked?

HH: Right! Not that I ever talked to Heinlein that much, we'd meet once a year at conventions and whatever. But I talked to Asimov and said: Isaac, have you read it? And he said: Harry, it was fun! I never thought about the carbon dioxide. Isaac was a gentleman and he had a sense of humour... the complete opposite reaction...

PT: Heinlein was ever-so-slightly pro-military in Starship Troopers, wasn't he?

HH: He had a navy commission and an army commission.

PT: In his book you weren't allowed to vote unless you'd served in the military - you hadn't earned the right to vote.

HH: Right. I remember reading that and thinking: I know a lot of veterans, and they're mostly all alcoholics or mad!

PT: Exactly the sort of people you want to influence how a country is run!

HH: We're talking about the survivors of the draft here. A lot of them couldn't even read or write! In the Second World War, Korea, and Vietnam - it got worse with each one - the guys who got drafted were those who couldn't do anything else: they couldn't get into college or whatever.

Did you see the film of Starship Troopers? It really is hysterical. Pro-Fascist... you're never sure what's going on, but the bugs are great, great effects.

PT: It's a tough book to read now, isn't it?

HH: I reread it some years ago... it's his first polemic book, the first book where he stops the action to lecture you.

PT: There's some nice stuff in the story, but the politics are...

HH: The survival suits are great, the mechanisms are good... except the atomic grenades. I read an article recently where some guy talking about atomic shells for big guns, cannons, you know? And there was a military man saying: Atomic shells? That's about as intelligent as suggesting an atomic hand grenade! But Heinlein had them! The minimum yield for an atomic weapon is equivalent to about some thousand of tons of dynamite: if you take it below that it won't explode.

PT: I think Joe Haldeman does the whole thing much better in The Forever War.

HH: That came out originally as novelettes in Astounding and I put all three of them in the Year's Best as they came out.

PT: Bill, the Galactic Hero was published in the mid-Sixties, but military thinking hasn't changed much since then has it?

HH: The military is exactly the same as it ever was, totally stratified: you accept orders from the top, don't think below that. It's degrading in every way.

The only thing I think that's happened to the military... When I was in the military they had segregation - in the South, not in New York - separate barracks, separate army for blacks and whites. Blacks weren't allowed to carry guns: they were afraid they'd shoot there officers if they did, because all the officers were white. They were in work battalions - they drove trucks, the eight-ball express - and engineering battalions. No guns!

Then, three or four years after the war, Harry Truman became president after Roosevelt died, and he had been a captain in the artillery in the First World War. He said: You will eliminate segregation in the army tomorrow at 0600 hours. The racist outfits in the army - mostly in the South - didn't want to do it, they hated it, but they did it.

PT: The order came from the top...

HH: ... and you've got to obey it. But then what happened in Vietnam was the army was about 90% black, because these poor guys couldn't go and join the National Guard like Bush did, they didn't have any way of getting out of the draft.

PT: You were drafted in 1943, and sent off to basic training when you were eighteen years old...

HH: In America - unlike England - you have to go to school until you're eighteen, and at eighteen you graduated high school. The draft age was eighteen. I was of the draftee generation: the war started in '41, I graduated in '43, so I spent three years just waiting to be drafted.

They had a really good physical examination: they shone a torch up your ass and looked down your throat, and if they didn't see light, you were in!

I was talking about this the other day: some of the draft scenes were so disgusting that when I did Bill, the Galactic Hero I had to leave them out. They were too filthy to use in those days!

All the draftees were stripped - starkers! - apart from your shoes, so you didn't get chewing gum stuck to the soles of your feet. We all had medical orders, and they'd march you up and down, all around this big building for examination, and you'd show them the folder and they'd write something on it. The Grand Central Palace in New York had giant lifts that would take thirty or forty people: the doors opened up, and across the room were about a hundred girls all typing away -- [Mimes covering groin with medical orders and looking at the ceiling] -- and then the doors closed.

The proctologist - with masks and gloves on - would do ten guys at a time: Bend over and spread your cheeks! He'd run along the line with a torch looking up their arseholes seeing if anything was hanging out. That's it, Next!

They tested for diabetes. We went into a room with duck boards on the floor, and there was a medic in gloves and mask, whites stained yellow! You pass him urine samples to test and he's swirled them around to see if they change colour, and there's piss everywhere!

You couldn't put that in the book, but it was true.

One I did use - which was absolutely true - was when we had to go and get our shots. There were guys on each side with needles, and bang! [Jabbing motions with both hands] two shots at a time, and they'd push you in the back, then you would lean on a rail and bang! They'd vaccinate you. And this one guy got there, a big, well-made guy, and his eyes rolled up and he collapsed on the floor. But this being the military, they gave him his shots, dragged him forward three feet, two more shots, dragged him forward... You can't exaggerate that, because you can't make it any worse!

So the material was there. I used an awful lot of this original stuff, but some I had to leave out.

PT: Was there a Deathwish Drang during your military training?

HH: No, but there were these perpetual sergeants. These guys were models of military incompetence. I taught literacy when I was in Mississippi: we'd finished basic training and I was waiting for shipment. I had a high school degree, so I ended up teaching basic literacy. And I had a Master Sergeant in the class: he'd managed to get up to the highest rank for a non-com - been there twenty years - by saying: I forgot my glasses, read this for me will you? He'd become the first sergeant in the outfit and was unable to read!

This is what our sergeants were like. We had a corporal who would say: As you was! Because he thought that was the correct way of saying As you were.

PT: What was basic training like?

HH: The military policy, in basic training, was to break you down as far as they could break you. And if you died, that was unimportant. If you went Section 8 - medical discharge for insanity reasons - that was unimportant. They wanted you to go Section 8, to have a breakdown, in basic training to save a lot of money and wasted time, so you wouldn't break down in combat. It was a very logical idea from the military point of view.

We had two guys Section 8 out. There was one Jewish kid my age, eighteen, and I watched this kid fall apart emotionally. He couldn't take the military, couldn't take the pressures of lack of sleep and everything, and he was getting weepier and weepier, and one day they took him away, and he went Section 8.

PT: And that probably screwed him up for the rest of his life.

HH: That was his life completely wrecked. I saw it again when I was in California: Vietnam was going on, and the draft. There was a young science fiction writer called Robert Taylor, like the actor. I published a story of his in an anthology - he lived near us in San Diego, and he was taking a degree to teach English. He was a friend of Moira's and came over to the house, and he said: They told me if I volunteer, I can pick my service, and they'll pay me to teach. I said: No, they're lying to you. As soon as they get your ass in the military, they'll do whatever they want with you. Don't do it. He went in, did basic training, sent into combat, had a nervous breakdown and came out Section 8. I saw him a year later and he was just shaking - not just his career, but his whole life was ruined.

The military do that. They're happy to do that.

PT: So how did you get through it?

HH: You have to be either so stupid that you get through it, or so intelligent that you know they're arseholes and you survive that way. You have to be a survivor, basically. You could go through your whole life without ever being tested that way...

The testing is physical, it's emotional, and you have to learn to take it. It's a very immoral organisation.

Physically if you're not in very good shape they can take you apart and rebuild you: I weighed only 150 pounds when I went in, a little more than 10 stone, and I went down about thirty pounds; then I went back up to 150 pounds - all muscle!

You had no sleep, endless exercise, rotten food... but if you ate the food, it was a balanced diet. You could have only one helping of meat - if they had meat that day - but you could have all you wanted of the vegetables, the bread, the pudding and the rest of it, so you could eat until you were full. It was filthy stuff, but there was enough of it so you could stay alive.

PT: This is basically so that if you're in combat and they give you an order, you obey without question?

HH: Yeah, so you never question them. But the thing was, for me, I had to survive basic training, but then they sent me to technical school to learn about computers: after that it was the usual army crap, but they had to keep us alive because we were doing technical stuff. But we still had to do KP...

PT: What does KP stand for?

HH: Kitchen Police. The military never hired civilians to work in the kitchen, so everyone serves KP. How often depends on the size of the outfit. Where I was it was once a month.

You would tie a knot on the end of your bed, and at three o'clock the orderly would come round and see it and wake you up for KP. The army turned out the lights at 10 o'clock, so you'd go to bed at ten. But the guys would turn them on again and play poker until 11.30 or 12 o'clock, so you'd only get two or three hours sleep. You'd work from three in the morning until seven at night. You'd be in the chow hall from four o'clock, and it'd be like the tropics, and you'd be scrubbing pans. Any labour that's repetitive is pretty hard in that kind of heat.

Once I was breaking eggs for omelettes into a thirty gallon pot. Breaking eggs isn't such a big job, you learn to do one in each hand; you break them into a bowl first, and if there's any blood in them you throw them away, that way you don't spoil the whole pot. But it was about eight-five degrees in the kitchen, it was still dark, and I was covered in egg, and after a while you couldn't move your hands, they were coated solid with egg!

There were coal-fired stoves - by now it was ninety-five to a hundred degrees in the kitchen, and I'm making egg toast. You ever made egg toast? Dip bread in egg, fry it, turn it over. I laid them out on a stove about a yard square, and they had the heat so high that by the time I'd covered the square I'd have to go back and turn them straight over, then go back and take them off. You do that for two hours, it's like some kind of torture. And you work until seven at night, then the next day back to the guns.

PT: From what you've said elsewhere, military life wasn't just tiring, it was also mind-numbingly dull?

HH: I was brain dead! I'd been through the tech school and now I was working a seven day week, and I was doing four men's jobs. Literally.

When I first started on the gunnery range we had these two-and-a-half ton trucks, with a welded frame and a power turret mounted on them, with two machine guns. This was for the last week of training for gunners, when they got to fire live rounds. To hear a .50 is a horrible sound: you can't move, it vibrates your whole body.

They driver would drive the truck out to the driving range, back it in, jack it up. The armourer would put the guns in, sight them, get the ammunition in; then I'd work on the computer and get that aligned; and then the instructor would instruct.

Well, after about two weeks they decided that anyone would drive a goddamn truck, so the driver was sent off overseas! About a week-and-a-half later they realised that as a power-operated turret and computer gunsight specialist I also had an armourer rating: I could service calibre fifties... so the armourer was sent overseas!

Now we have two guys left. I was driving the truck; taking the guts out of the gun and cleaning it, loading the ammunition, aligning the gunsight. And after about a month or two I knew as much about the thing as the instructor did: they didn't need the instructor anymore, and he was off overseas!

So I'd be up at four in the morning, driving to the range at five, the guns would be banging away all morning; then stop while we had a bit of chow, banging away until five, drive the truck back. You'd be too tired to do anything in the evening except go to sleep.

So I was brain dead because there was no intelligence involved anywhere along the line.

We'd get up in a morning and we'd have about an hour before we had to drive thirty miles out into the desert to the firing range. And when the concrete was still cool from the night, I'd be lying under the truck where no one could see me, reading Dostoevsky! Until the sun came up and it got too hot.

That's when I got the Esperanto book too - I had to do something with my brain.

PT: Towards the end of the war you ended up as a Military Policeman, how did that come about?

HH: The war was almost over, I was based in Laredo, Texas, but they were closing the gunnery school down. I was a 678-3 - Power-Operated Turret and Gunsight Specialist - the 3 meant skilled. I worked with computers, and I was a sergeant. And still pulling KP!

There was only one airbase gunnery school still working: Panama City, Florida. I had to take the train down to Dothan, Alabama, and then to the field by the coach. By the time I got there, they'd closed that one down too! But I was still assigned there. I went to see the detail sergeant and said: What do I do, sergeant? He said: The training school has closed down, so it's either permanent KP or MP. So I said [through gritted teeth]: I've always wanted to carry a gun for my country! So I became an MP.

And the MP's were all crackers from the South, all Rebels, you know, all morons, all illiterate. And they gave me what they thought was the worst job: they gave me the 'nigger' stockade. It was the greatest experience of my life!

All these black guys were from the North, and they were all on company punishment. There were two kinds of punishment in the army: court martial, where they needed a trial and witnesses, and company punishment. All of the officers were white, and these guys had basically told an officer to go fuck himself, and they'd got maximum company punishment of just under a year, 364 days, because that meant no trial.

All of these guys were just trying to finish their sentences and get an honourable discharge, because then they'd be entitled to go to school on the G.I. Bill and get retirement benefits, which they wouldn't get with a dishonourable discharge. So they weren't going to give me any trouble. I'd get them to hold my shotgun while I ate in the black mess hall!

I was riding shotgun on a garbage truck. I'd sit in a seat welded to the cab with my shotgun, and we'd go around all the mess halls picking up the garbage.

One thing about the white army: if a chef came in, they made him a rifleman. They get some kid from the south, someone who literally hadn't worn shoes until he got into the army, and make him a cook. But they thought all Negroes were alike, the cook in the black mess hall was the head chef from the Waldorf Astoria. Boy did we eat well!

I'd give one of my prisoners my shotgun to hold and say: I'm eating first!

In the army you learn to curse, chase girls, and drink - in whatever order. Cursing is the first thing you learn in the army: a lot of civvy expressions like 'it's a crock', meaning it's a crock of shit, come from the army. Snafu is from the army too, meaning situation normal: all fucked up.

It got so repetitive that when a guy got out of the army he couldn't say three words without saying fuck: I took a fucking bus into fucking town, met a fucking girl in a fucking bar, took her out and had intercourse!

Harry Turtledove, in one of his books about the Civil War has one of his white characters turn round and say "You motherfucker!" [Shakes his head] No, no, Harry. I imported that word into the English language! One of the black prisoners said: Get out of here, you motherfucker. This was November 1945. I'd never heard it before, and I'd heard every single word! Harry Turtledove had it in 1861 - no way!

I said it to another white sergeant, and within about a week I was hearing it from all sides!

I'm the guy who imported 'motherfucker' into the English language - they should have me in the OED!

I have got 18 entries in the Oxford English Dictionary. There's one entry for a Harry Harrison in 1600 or 1800, but the rest are mine. One of them is knorr, a wide-beamed Viking ship from The Technicolor Time Machine. I also have ginzo, also from Technicolor Time Machine, which is New York slang for an Italian. And 15 other ones which are cited as references.

PT: Did you ever worry that the army would turn you into one of those grizzled, cynical, cruel officers you've written about?

HH: Oh, no, no! Much the opposite. I was a non-com, don't forget, doing a technical job. And hated the army.

When I finally got discharged, I remember it was the first time that anyone ever spoke to me kindly. I was getting my discharge a Fort Lee, New Jersey. I went in with my discharge papers and passed the queue of officers trying to re-enlist which went round the block. Easy job!

PT: What else were they going to do if they left the army?

HH: Nothing! They were all kids right out of high school. Most of them were flyers - you had to be a Second Lieutenant to fly.

And I got into a very short queue. And when I got to the desk, the sergeant said: Sit down please, will you, sergeant. And I thought: What's this? What's this?

He said: I see it took you three years to make sergeant. I said: Yeah, I was frozen in category and grade, that's why. I wanted more money, and they wouldn't give it to me.

Re-enlist, he said. Tech in one month; Staff in three months, by the time six months go by you'll be a Master Sergeant - which is the highest non-com rank. And I burst out laughing. And guys on either side of me were laughing like shit and walking out. We were out, all they had to do was stamp our papers.

The Air Corps in those days was just getting technical. They'd just brought in the B-29, and they took me out to look at it. Don't forget, our computers were mechanical - gears and cam followers - and the biggest problem we had was backlash in the gear train: when a gear train reverses there is a space between each cog wheel that must be taken up before the next gear moves and this causes an error in the readout. So we spring-loaded gears to take up this slack... and that was the only problem I can remember.

The B-29 had CFC - central firing control - which was completely electronic. They took up the floor, opened the box, and it was full of thermionic valves, radio tubes. I said: Christ, where are the gears? They had four gun turrets, remote controlled... no way!

They wanted people. I had a good technical rating, and they wanted me in. But I wanted out.

When I went in, the Air Corps was something like 60 or 70 guys on the ground for one in the air. Now there are 420 on the ground for one in the air.

PT: Things weren't that easy when you got out of the army, were they?

HH: It was a lot harder than I realised. It's a completely different world: you go in when you're eighteen, when you're a kid. Kids stay younger in the States than they are here, they aren't allowed to mature until after they're eighteen.

I was head of the library in high school, and I went back after the war to see the librarian, and I didn't realise it at the time, but they treat eighteen-year-olds there like little kids.

After three years in the army - drinking, chasing girls, cursing, all the usual stuff - I was a good non-com, I was completely adjusted to the army - I hated it, but I was completely adjusted to it in every way.

You were a kid before you went in, you're now a non-commissioned army officer, and there are no rules to follow in civilian life. What do you do? Except drink, of course. We drank a lot. You had an allowance that you were entitled to - 'Readjustment Allowance' - we called it the 52-20 Club: $20 a week for 52 weeks, and we'd drink it! Every Friday go down and get the check then use it for beer.

It was hard to readjust. You wouldn't think so, but you had to adjust to a totally different environment where you don't know the rules.

PT: You had a couple of dead-end jobs after leaving the army, didn't you?

HH: Oh, yeah. I didn't know what to do at all. I worked for Waldes-Kohinoor who made pliers for slip rings and it was a great job!

You'd have half a plier and you'd put it on a hydraulic press, and so you didn't get your hands chopped off, you had to press it down with both hands. Then you'd take it out and put another one in. At the machine next to me was a Polish woman who'd been doing this for seventeen years: I lasted three days!

I went to see the girl in the office and she said: Mr. Harrison, you've only been here three days, aren't you happy here? Aargh! [Makes strangling motions] After that they had me bending pliers for a bit.

I went to art school then - I got $50 a month subsistence allowance. I hung a stamped pliers half on my Dazor lamp, and at three in the morning when I was tired, I'd look at them and think: Aaargh! Draw faster, draw faster!

I went to a couple of art schools: I went to Hunter College for a bit and did art. Studied with John Blomshield - I have one of his paintings over there - a very fine American artists, a Mannerist who was in Paris in the '30s with all the other painters. And I went to Burne Hogarth's art school learning comic art.

Bill, the Galactic Hero

© Harry Harrison 1965

Art: Harry Harrison (New Worlds, August 1965)

Chapter One

Bill never realised that sex was the cause of it all. If the sun that morning had not been burning so warmly in the brassy sky of Phigerinadon II, and if he had not glimpsed the sugar-white and barrel-wide backside of Inga-Maria Calyphigia while she bathed in the stream, he might have paid more attention to his ploughing than to the burning pressures of heterosexuality, and would have driven his furrow to the far side of the hill before the seductive music sounded along the road. He might never have heard it and his life would have been very, very different. But he did hear it and dropped the handles of the plough that was plugged into the robomule, turned and gaped.It was indeed a fabulous sight. Leading the parade was a one-robot band, twelve feet high and splendid in its great black busby that concealed the hi-fi speakers. The golden pillars of its legs stamped forward as its thirty articulated arms sawed, plucked and fingered at a dazzling variety of instruments. Martial music poured out in wave after inspiring wave and even Bill's thick peasant feet stirred in their clodhoppers as the shining boots of the squad of soldiers crashed along the road in perfect unison. Medals jingled on the manly swell of their scarlet-clad chests and there could certainly be no nobler sight in all the world. To their rear marched the sergeant, gorgeous in his braid and brass, thickly clustered medals and ribbons, sword and gun, girdled gut and steely eye which sought out Bill where he stood gawking over the fence. The grizzled head nodded in his direction. the steel-trap mouth bent into a friendly smile and there was a conspiratorial wink. Then the little legion was past, and hurrying behind in their wake came a huddle of dust-covered ancillary robots, hopping and crawling or rippling along on treads. As soon as these had gone by Bill climbed clumsily over the split-rail fence and ran after them. There were no more than two interesting events every four years here, and he was not going to miss what promised to be a third.

A crowd had already gathered in the market square when Bill hurried up, and they were listening to an enthusiastic band concert. The robot hurled itself into the glorious measures of Star Troopers to the Skies Avaunt, and thrashed its way through Rockets Rumble and almost demolished itself in the tumultuous rhythm of Sappers at the Pithead Digging. It pursued this last tune so strenuously that one of its legs flew off, rising high into the air, but was caught dextrously before it could hit the ground and the music ended with the robot balancing on its remaining leg beating time with the detached limb. It also, after an ear-fracturing peal on the brasses, used the leg to point across the square to where a tri-di screen and refreshment booth had been set up. The troopers had vanished into the tavern and the recruiting sergeant stood alone among his robots, beaming a welcoming smile.

"Now hear this! Free drinks for all, courtesy of the Emperor, and some lively scenes of jolly adventure in distant climes to amuse you while you sip," he called in an immense and leathery voice.

Most of the people drifted over, Bill in their midst, though a few embittered and elderly draft-dodgers slunk away between the houses. Cooling drinks were shared out by a robot with a spigot for a navel and an inexhaustible supply of plastic glasses in one hip. Bill sipped his happily while he followed the enthralling adventures of the space troopers in full colour with sound effects and stimulating subsonics. There was battle and death and glory though it was only the Chingers who died: troopers only suffered neat little wounds in their extremities that could be covered easily by small bandages. And while Bill was enjoying this, Recruiting Sergeant Grue was enjoying him, his little piggy eyes ruddy with greed as they fastened on to the back of Bill's neck.

This is the one! he chortled to himself while, unknowingly, his yellowed tongue licked at his lips. He could already feel the weight of the bonus money in his pocket. The rest of the audience were the usual mixed bag of overage men, fat women, beardless youths and other unenlistables. All except this broad-shouldered, square-chinned, curly-haired chunk of electronic cannon-fodder. With a precise hand on the controls the sergeant lowered the background subsonics and aimed a tight-beam stimulator at the back of his victim's head. Bill writhed in his seat, almost taking part in the glorious battle unfolding before him.

As the last chord died and the screen went blank the refreshment robot pounded hollowly on its metallic chest and bellowed DRINK! DRINK! DRINK! The sheeplike audience swept that way, all except Bill who was plucked from their midst by a powerful arm.

"Here, I saved some for you," the sergeant said, passing over a prepared cup so loaded with dissolved ego-reducing drugs that they were crystalising out at the bottom. "You're a fine figure of a lad and to my eye seem a cut above the yokels here. Did you ever think of making your career in the forces?"

"I'm not the military type, shargeant..." Bill chomped his jaws and spat to remove the impediment to his speech, and puzzled at the sudden fogginess in his thoughts. Though it was a tribute to his physique that he was even conscious after the volume of drugs and sonics that he had been plied with. "Not the military type. My fondest ambition is to be of help in the best way I can, in my chosen career as a Technical Fertiliser Operator and I'm almost finished with my correspondence course..."

"That's a crappy job for a bright lad like you," the sergeant said while clapping him on the arm to get a good feel of his biceps. Rock. He resisted the impulse to pull Bill's lip down and take a quick peek at the condition of his back teeth. Later. "Leave that kind of job to those that like it. No chance of promotion. While a career in the troopers has no top. Why Grand-Admiral Pflunger came up through the rocket tubes, as they say, from Recruit Trooper to Grand-Admiral. How does that sound?"

"It sounds very nice for Mr Pflunger but I think fertiliser operating is more fun. Gee - I'm feeling sleepy. I think I'll go lie down."

"Not before you've seen this, just as a favour to me of course," the sergeant said, cutting in front of him and pointing to a large book hold open by a tiny robot. "Clothes make the man and most men would be ashamed to be seen in a crummy looking smock like that thing draped around you or wearing those broken canalboats on their feet. Why look like that when you can look like this?"

Bill's eyes followed the thick finger to the colour plate in the book where a miracle of misapplied engineering caused his own face to appear on the illustrated figure dressed in trooper-red. The sergeant flipped the pages and on each plate the uniform was a little more gaudy, the rank higher. The last one was that of a Grand-Admiral and Bill blinked at his own face under the plumed helmet, now with a touch of crowfeet about the eyes and sporting a handsome and grey-shot moustache, but still undeniably his own.

"That's the way you will look," the sergeant murmured into his ear, "once you have climbed the ladder of success. Would you like to try a uniform on. Tailor!"

When Bill opened his mouth to protest the sergeant put a large cigar into it, and before he could get it out the robot tailor had rolled up, swept a curtain bearing arm about him and stripped him naked. "Hey! Hey... !" he said.

"It won't hurt," the sergeant said, poking his great head through the curtain and beaming at Bill's muscled form. He poked a finger into a pectoral (rock) then withdrew.

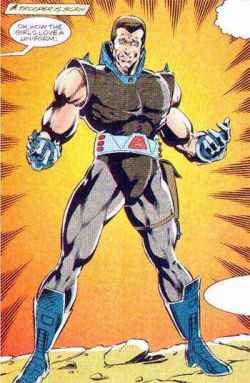

"Ouch!" Bill said as the tailor extruded a cold pointer and jabbed him with it, measuring his size. Something went chunk deep inside its tubular torso and a brilliant red jacket began to emerge from a slot in the front. In an instant this was slipped on to Bill and the shining gold buttons buttoned. Luxurious grey moleskin trousers were pulled on next, then gleaming black knee-length boots. Bill staggered a bit as the curtain was whipped away and a powered full-length mirror rolled up.

"Oh how the girls love a uniform," the sergeant said, "and I can't blame them."

A memory of the vision of Inga-Maria Calyphigia's matched white moons obscured Bill's sight for a moment, and when it had cleared he found he was grasping a stylo and was about to sign the form that the recruiting sergeant held before him.

"No," Bill said, a little amazed at his own firmness of mind. "I don't really want to. Technical Fertilizer Operator..."

"And not only will you receive this lovely uniform, an enlistment bonus and a free medical examination, but you will he awarded these handsome medals." The sergeant took a flat box, offered to him on cue by a robot, and opened it to display a glittering array of ribbons and bangles. "This is the Honourable Enlistment Award," he intoned gravely, pinning a jewel-encrusted nebula, pendant on chartreuse, to Bill's wide chest. "And the Emperor's Congratulatory Gilded Horn, the Forward to Victory Starburst, the Praise Be Given Salutation of the Mothers of the Victorious Fallen and the Everflowing Cornucopia which does not mean anything but it looks nice and can be used to carry contraceptives." He stepped back and admired Bill's chest which was now adangle with ribbons, shining metal and gleaning paste gems.

"I just couldn't," Bill said. "Thank you anyway for the offer, but..."

The sergeant smiled, prepared even for this eleventh hour resistance, and pressed the button on his belt that actuated the programmed hypno-coil in the heel of Bill's new boot. The powerful neural current surged through the contacts and Bill's hand twitched and jumped, and when the momentary fog had lifted from his eyes he saw that he had signed his name.

"But..."

"Welcome to the Space Troopers," the sergeant boomed, smacking him on the back (trapezium like rock) and relieving him of the stylo. "FALL IN!" in a larger voice, and the recruits stumbled from the tavern.

"What have they done to my son!" Bill's mother screeched, coming into the market square, clutching at her bosom with one hand and towing his baby brother Charlie with the other. Charlie began to cry and wet his pants.

"Your son is now a trooper for the greater glory of the Emperor," the sergeant said, pushing his slack-jawed and round-shouldered recruit squad into line.

"No! it can't be..." Bill's mother sobbed, tearing at her greying hair. "I'm a poor widow, he's my sole support... you cannot...!"

"Mother..." Bill said, but the sergeant shoved him back into the ranks.

"Be brave, madam," he said. "There can be no greater glory for a mother." He dropped a large and newly minted coin into her hand. "Here is the enlistment bonus, the Emperor's shilling, I know he wants you to have it. ATTENTION!"

With a clash of heels the graceless recruits braced their shoulders and lifted their chins. Much to his surprise, so did Bill.

"RIGHT TURN!"

In a single, graceful motion they turned as the command robot replayed the order to the hypno-coil in every boot. FORWARD MARCH! And they did in perfect rhythm, so well under control that, try as hard as he could, Bill could neither turn his head nor wave a last goodbye to his mother. She vanished behind him and one last anguished wail cut through the thud of marching feet.

"Step up the count to 130," the sergeant ordered, glancing at the watch set under the nail of his little finger. "Just ten miles to the station and we'll be in camp tonight, my lads."

The command robot moved its metronome up one notch and the tramping boots conformed to the smarter pace and the men began to sweat. By the time they had reached the copter station it was nearly dark, their red paper uniforms hung in shreds, the gilt had been rubbed from their pot metal buttons and the surface charge that repelled the dust from their thin plastic boots had leaked away. They looked as ragged, weary, dusty and miserable as they felt.

Chapter Two

It wasn't the recorded bugle playing reveille that woke Bill, but the supersonics that streamed through the metal frame of his bunk that shook him until the fillings vibrated from his teeth. He sprang to his feet and stood there shivering in the grey of dawn. Because it was summer the floor was refrigerated: no mollycoddling of the men in Camp Leon Trotsky. The pallid, chilled figures of the other recruits loomed up on every side, and when the soul-shaking vibrations had died away they dragged their thick sackcloth and sandpaper fatigue uniforms from their bunks, pulled them hastily on, jammed their feet into the great purple recruit boots and staggered out into the dawn.

"I am here to break your spirit," a voice, rich with menace, told them, and they looked up and shivered even more as they faced the chief demon in this particular hell.

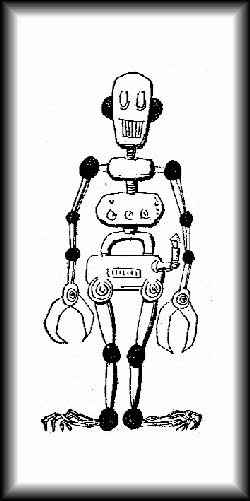

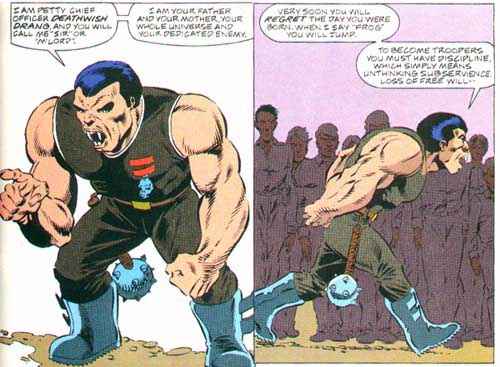

Art: Harry Harrison (New Worlds, August 1965)

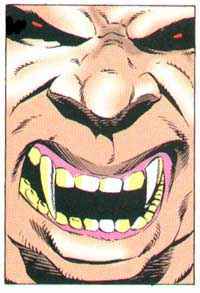

Petty Chief Officer Deathwish Drang was a specialist from the tips of the angry spikes of his hair to the corrugated stamping-soles of his mirror-like boots. He was wide shouldered and lean hipped, while his long arms hung curved like some horrible anthropoid, the knuckles of his immense fists scarred from the breaking of thousands of teeth. It was impossible to look at this detestable form and imagine that it issued from the tender womb of a woman. He could never have been born; he must have been built to order by the government. Most terrible of all was the head. The face! The hairline was scarcely a finger's-width above the black tangle of the brows that were set like a rank growth of foliage at the rim of the black pits that concealed the eyes - visible only as baleful red gleams in the stygian darkness. A nose broken and crushed, squatted above the mouth that was like a knife slash in the taut belly of a corpse, while from between the lips issued the great, white fangs of the canine teeth, at least two inches long, that rested in grooves on the lower lip.

"I am Petty Chief Officer Deathwish Drang and you will call me 'Sir' or 'M'lord'." He began to pace grimly before the row of terrified recruits. "I am your father and your mother and your whole universe and your dedicated enemy, and very soon I will have you regretting the day you were born. I will crush your will. When I say frog you will jump. My job is to turn you into troopers, and troopers have discipline. Discipline means simply unthinking subservience, loss of free will, absolute obedience. That is all I ask..."

He stopped before Bill. who was not shaking quite as much as the others, and scowled.

"I don't like your face. One month of Sunday KP."

"Sir..."

"And a second month for talking back."

He waited, but Bill was silent. He had already learned his first lesson on how to he a good trooper. Keep your mouth shut. Deathwish paced on.

"Right now you are nothing but horrible, sordid, flabby pieces of debased civilian flesh. I shall turn that flesh into muscle, your wills to jelly, your minds to machines. You will become good troopers or I will kill you. Very soon you will be hearing stories about me, vicious stories about how I killed and ate a recruit who disobeyed me."

He halted and stared at them, and slowly the coffin-lid lips parted in an evil travesty of a grin, while a drop of saliva formed at the tip of each whitened tusk.

"That story is true."

A moan broke from the row of recruits and they shook as though a chill wind had passed over them. The smile vanished.

"We will run to breakfast now as soon as I have some volunteers for an easy assignment. Can any of you drive a helicar?"

Two recruits hopefully raised their hands and he beckoned them forward. "All right, both of you, mops and buckets behind that door. Clean out the latrine while the rest are eating. You'll have a better appetite for lunch."

That was Bill's second lesson on how to be a good trooper: never volunteer.

The days of recruit training passed with a horribly lethargic speed. With each day conditions became worse and Bill's exhaustion greater. This seemed impossible, but it was nevertheless true. A large number of gifted and sadistic minds had designed it to be that way. The recruits' heads were shaved for uniformity and their genitalia painted with orange antiseptic to control the endemic crotch crickets. The food was theoretically nourishing but incredibly vile and when, by mistake, one batch of meat was served in an edible state it was caught at the last moment and thrown out and the cook reduced two grades. Their sleep was broken by mock gas attacks and their free time filled with caring for their equipment. The seventh day was designated as a day of rest but they all had received punishments, like Bill's KP, and it was as any other day. On this, the third Sunday of their imprisonment, they were stumbling through the last hour of the day before the lights were extinguished and they were finally permitted to crawl into their I casehardened bunks. Bill pushed against the weak force field that blocked the door, cunningly designed to allow the desert flies to enter but not leave the barracks, and dragged himself in. After fourteen hours of KP his legs vibrated with exhaustion and his arms were wrinkled and pallid as a corpse's from the soapy water. He dropped his jacket to the floor, where it stood stiffly supported by its burden of sweat, grease and dust, and dragged his shaver from his footlocker. In the latrine he bobbed his head around trying to find a clear space in one of the mirrors. All of them had been heavily stencilled in large letters with such inspiring messages as KEEP YOUR WUG SHUT - THE CHINGERS ARE LISTENING and IF YOU TALK, THIS MAN MAY DIE. He finally plugged the shaver in next to WOULD YOU WANT YOUR SISTER TO MARRY ONE? and centred his face in the O in ONE. Black-rimmed and bloodshot eyes stared back at him as he ran the buzzing machine over the underweight planes of his jaw. It took more than a minute for the meaning of the question to penetrate his fatigue-drugged brain.,

"I haven't got a sister," he grumbled peevishly. "And if I did why should she want to marry a lizard anyway?" It was a rhetorical question but it brought an answer from the far end of the room, from the last shot tower in the second row.

"It doesn't mean exactly what it says - it's just there to make us hate the dirty enemy more."

Bill jumped, he had thought he was alone in the latrine, and the razor buzzed spitefully and gouged a bit of flesh from his lip.

"Who's there? Why are you hiding?" he snarled, then recognized the huddled dark figure and the many pairs of boots. "Oh, it's only you Eager." His anger drained away and he turned back to the mirror.

Eager Beager was so much a part of the latrine that you forgot he was there. A moon-faced, eternally smiling youth whose apple red cheeks never lost their glow, and whose smile looked so much out of place here in Camp Leon Trotsky that everyone wanted to kill him until they remembered that he was mad. He had to be mad because he was always eager to help his buddies and had volunteered as permanent latrine orderly. Not only that, but he liked to polish boots and had offered to do those of one after another of his buddies until now he did the boots for every man in the squad every night. Whenever they were in the barracks Eager Beager could be found crouched at the end of the thrones that were his personal domain, surrounded by the heaps of shoes and polishing industriously, his face wreathed in smiles. He would still be there after lights out, working by the light of a burning wick stuck in a can of polish, and was usually up before the others in the morning, finishing his voluntary job and still smiling. Sometimes, when the boots were very dirty, he worked right through the night. The kid was obviously insane but no one turned him in because he did such a good job on the boots and they all prayed that he wouldn't die of exhaustion until recruit training was finished.

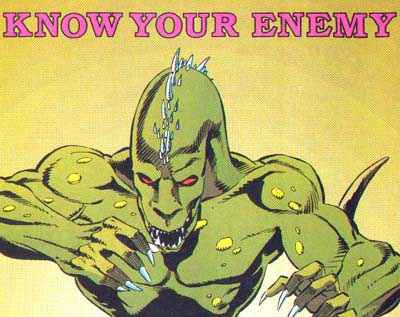

"Well if that's what they want to say, why don't they just say Hate the dirty enemy more?" Bill complained. He jerked his thumb at the far wall where there was a poster labelled KNOW THE ENEMY. It featured a life-size illustration of a Chinger, a seven foot high saurian that looked very much like a scale-covered, four-armed, green kangaroo with an alligator's head. "Whose sister would want to marry a thing like that anyway? And what would a thing like that want to do with a sister, except maybe eat her?"

Eager put a last buff on a purple toe and picked up another boot. He frowned for a brief instant to show what a serious thought this was. "Well you see, gee - it doesn't mean a - sister. It's just part of psychological warfare. We have to win the war. To win the war we have to fight hard. In order to fight hard we have to have good soldiers. Good soldiers have to hate the enemy. That's the way it goes. The Chingers are the only non-human race that has been discovered in the galaxy that has gone beyond the aboriginal level, so naturally we have to wipe them out."

"What the hell do you mean naturally? I don't want to wipe anyone out. I just want to go home and be a Technical Fertilizer Operator."

"Well I don't mean you personally, of course - gee!" Eager opened a fresh can of polish with purple-stained hands and dug his fingers into it. "I mean the human race, that's just the way we do things. If we don't wipe them out they'll wipe us out. Of course they say that war is against their religion and they will only fight in defence, and they have never made any attacks yet. But we can't believe them even though it is true. They might change their religion or their minds some day and then where would we be? The best answer is to wipe them out now."

Bill unplugged his razor and washed his face in the tepid, rusty water. "It still doesn't seem to make sense. All right, so the sister I don't have doesn't marry one of them. But how about that - " he pointed to the stencilling on the duck-boards, KEEP THIS SHOWER CLEAR - THE ENEMY CAN HEAR. "Or that - " The sign above the urinal that read BUTTON FLIES - BEWARE SPIES. "Forgetting for the moment we don't have any secrets here worth travelling a mile to hear, much less twenty-five light years - how could a Chinger possibly be a spy? What kind of make-up would disguise a seven foot lizard as a recruit? You couldn't even disguise one to look like Deathwish Drang, though you could get pretty close -"

The lights went out and, as though using his name had summoned him like a devil from the pit, the voice of Deathwish blasted through the barracks.

"Into your sacks! Into your sacks! Don't you lousy bowbs know there's a war on!"

Bill stumbled away through the darkness of the barracks where the only illumination was the red glow from Deathwish's eyes. He fell asleep the instant his head touched his carborundum pillow and it seemed that only a moment had elapsed before reveille sent him hurtling from his bunk. At breakfast, while he was painfully cutting his coffee-substitute into chunks small enough to swallow, the telenews reported heavy fighting in the Beta Lyra sector with mounting losses. A groan rippled through the mess hall when this was announced, not because of any excess of patriotism, but because any bad news would only make things worse for them. They did not know how this would be arranged, but they were positive it would be. They were right. Since the morning was a bit cooler than usual the Monday parade was postponed until noon when the ferroconcrete drill ground would have warmed up nicely and there would be the maximum number of heat prostration cases. But this was just the beginning. From where Bill stood at attention near the rear he could see that the air-conditioning canopy was up on the reviewing stand. That meant brass. The trigger guard of his atomic rifle dug a hole into his shoulder and a drop of sweat collected then dripped from the tip of his nose. Out of the corners of his eyes he could see the steady ripple of motion as men collapsed here and there, among the massed ranks of thousands, and were dragged to the waiting ambulances by alert corpsmen. Here they were laid in the shade of the vehicles until they revived and could be urged back to their positions in the formation.

Then the band burst into SPACEMEN HO AND CHINGERS VANQUISHED! and the broadcast signal to each boot heel snapped the ranks to attention at the same instant and the thousands of rifles flashed in the sun. The commanding general's staff car - this was obvious from the two stars painted on it - pulled up beside the reviewing stand and a tiny, round figure moved quickly through the furnacelike air to the comfort of the enclosure. Bill had never seen him any closer than this, at least from the front, though once while he was returning from late KP he had spotted the general getting into his car near the camp theatre. At least Bill thought it was he, but all he had seen was a brief rear view. Therefore, if he had a mental picture of the general, it was of a large backside superimposed on a teeny antlike figure. He thought of most officers in these general terms, since the men of course had nothing to do with officers during their recruit training. Bill had had a good glimpse of a 2nd lieutenant once, near the orderly room, and he knew he had a face. And there had been a medical officer who hadn't been more than thirty yards away, who had lectured them on venereal disease, but Bill had been lucky enough to sit behind a post and had promptly fallen asleep.

After the band shut up, the anti-G loudspeakers floated out over the troops and the general addressed them. He had nothing to say that anyone cared to listen to and he closed with the announcement that because of losses in the field their training programme would be accelerated, which was just what they had expected. Then the band played some more and they marched back to the barracks, changed into their haircloth fatigues and marched - double time now - to the range where they fired their atomic rifles at plastic replicas of Chingers that popped up out of holes in the ground. Their aim was very bad until Deathwish Drang popped out of a hole and every trooper switched to full automatic and hit with every charge fired from every gun, which is a very hard thing to do. Then the smoke cleared and they stopped cheering and started sobbing when they saw that it was only a plastic replica of Deathwish now torn to tiny pieces, and the original appeared behind them and gnashed its tusks and gave them all a full month's KP.

"The human body is a wonderful thing," Bowb Brown said a month later when they were sitting around a table in the Lowest Ranks Klub eating plastic-skinned sausages stuffed with road sweepings and drinking watery warm beer. Bowb Brown was a thoat herder from the plains, which is why they called him Bowb since everyone knows just what thoat-herders do with their thoats. He was tall, thin and bowlegged, his skin burnt to the colour of ancient leather. He rarely talked, being more used to the eternal silence of the plains broken only by the eerie cry of the restless thoat, but he was a great thinker since the one thing he had plenty of was time to think in. He could worry a thought for days, even weeks, before he mentioned it aloud, and while he was thinking about it nothing could disturb him. He even let them I call him Bowb without protesting: call any other trooper Bowb and he would hit you in the face. Bill and Eager and the other troopers from X squad sitting around the table all clapped and cheered, as they always did when Bowb said something.

"Tell us more, Bowb!"

"It can still talk - I thought it was dead!"

"Go on - why is the body a wonderful thing?"

They waited in expectant silence while Bowb managed to tear a bite from his sausage and, after ineffectual chewing, swallowed it with an effort that brought tears to his eyes. He eased the pain with a mouthful of beer and spoke.

"The human body is a wonderful thing because if it doesn't die it lives."

They waited for more until they realized that he was finished, then they sneered.

"Boy, are you full of bowb!"

"Sign up for OCS!"

"Yeah - but what does it mean?"

Bill knew what it meant, but didn't tell them. There were only half as many men in the squad as there had been the first day. One man had been transferred, but all the others were in the hospital, or in the mental hospital, or discharged for the convenience of the government as being too crippled for active service. Or dead. The survivors, after losing every ounce of weight not made up of bone or essential connective tissue, had put back the lost weight in the form of muscle and were now completely adapted to the rigours of Camp Leon Trotsky, though they still loathed it. Bill marvelled at the efficiency of the system. Civilians had to fool around with examinations, grades, retirement benefits, seniority and a thousand other factors that limited the efficiency of the workers. But how easily the troopers did it! They simply killed off the weaker ones and used the survivors. He respected the system. Though he still loathed it.

"You know what I need, I need a woman," Ugly Ugglesway said.

"Don't talk dirty," Bill told him promptly, since he had been correctly brought up.

"I'm not talking dirty!" Ugly whined. "It's not like I said I wanted to re-enlist or that I thought Deathwish was human or anything like that. I just said I need a woman. Don't we all ?"

"I need a drink," Bowb Brown said as he took a long swig from his glass of dehydrated reconstituted beer, shuddered, then squirted it out through his teeth in a long stream on to the concrete, where it instantly evaporated.

"Affirm, affirm," Ugly agreed, bobbing his mat-haired warty head up and down. "I need a woman and a drink." His whine became almost plaintive. "After all, what else is there to want in the troopers outside of out?"

They thought about that a long time, but could think of nothing else that anyone really wanted. Eager Beager looked out from under the table where he was surreptitiously polishing a boot and said that he wanted more polish, but they ignored him. Even Bill, now that he put his mind to it, could think of nothing he really wanted other than this inextricably linked pair. He tried hard to think of something else, since he had vague memories of wanting other things when he had been a civilian, but nothing else came to mind.

"Gee, it's only seven weeks more until we get our first pass," Eager said from under the table, then screamed a little as everyone kicked him at once.

But slow as subjective time crawled by, the objective clocks were still operating and the seven weeks did pass by and eliminate themselves one by one. Busy weeks filled with all the essential recruit training courses: bayonet drill, small-arms training, short-arm inspection, greypfing, orientation lectures, drill, communal singing and the Articles of War. These last were read with dreadful regularity twice a week and were absolute torture because of the intense somnolence they brought on. At the first rustle of the scratchy, monotonous voice from the tape player heads would begin to nod. But every seat in the auditorium was wired with an EEG that monitored the brain waves of the captive troopers. As soon as the shape of the Alpha wave indicated transition from consciousness to slumber a powerful jolt of current would be shot into the dozing buttocks, jabbing the owner painfully awake. The musty auditorium was a dimly lit torture chamber, filled with the droning dull voice punctuated by the sharp screams of the electrified, the sea of nod ding heads abob here and there with painfully leaping figures.

No one ever listened to the terrible executions and sentences announced in the Articles for the most innocent of crimes. Everyone knew that they had signed away all human rights when they enlisted, and the itemising of what they had lost interested them not in the slightest. What they really were interested in was counting the hours until they would receive their first pass. The ritual by which this reward was begrudgingly given was unusually humiliating, but they expected this and merely lowered their eyes and shuffled forward in the line, ready to sacrifice any remaining shards of their self-respect in exchange for the crimpled scrap of plastic. This rite finished, there was a scramble for the monorail train whose track ran on electrically charged pillars, soaring over the thirty-foot-high barbed wire, crossing the quicksand beds, then dropping into the little farming town of Leyville.

At least it had been an agricultural town before Camp Leon Trotsky had been built and sporadically, in the hours when the troopers weren't on leave, it followed its original agrarian bent. The rest of the time the grain and feed stores shut down and the drink and knocking shops opened. Many times the same premises were used for both functions. A lever would be pulled when the first of the leave party thundered out of the station and the grain bins became beds, sales clerks pimps, cashiers retained their same function - though the prices went up - while the counters would be racked with glasses to serve as bars. It was to one of these establishments, a mortuary-cum-saloon, that Bill and his friends went.

"What'll it be, boys?" the ever-smiling owner of the Final Resting Bar and Grill asked.

"Double shot of Embalming Fluid." Bowb Brown told him.

"No jokes," the landlord said, the smile vanishing for a second as he took down a bottle on which the garish label REAL WHISKY had been pasted over the etched-in EMBALMING FLUID. "Any trouble I call the MPs." The smile returned as money struck the counter. "Name your poison, gents."

They sat around a long, narrow table as thick as it was wide with brass handles on both sides, and let the blessed relief of ethyl alcohol trickle a path down their dust-lined throats.

"I never drank before I came into the service," Bill said, draining four fingers neat of Old Kidney Killer, and held his glass out for more.

"You never had to," Ugly said, pouring.

"That's for sure," Bowb Brown said, smacking his lips with relish and raising a bottle to his lips again.

"Gee," Eager Beager said, sipping hesitantly at the edge of his glass. "It tastes like a tincture of sugar, wood chips, various esters and a number of higher alcohols."

"Drink up," Bowb said incoherently around the neck of the bottle. "All them things is good for you."

"Now I want a woman," Ugly said and there was a rush as they all jammed in the door trying to get out at the same time, until someone shouted Look! and they turned to see Eager still sitting at the table.

"Woman!" Ugly said enthusiastically, in the tone of voice you say Dinner! when you are calling a dog. The knot of men stirred in the doorway and stamped their feet. Eager didn't move.

"Gee - I think I'll stay right here," he said, his smile simpler than ever. "But you guys run along."

"Don't you feel well, Eager?"

"Feel fine."

"Ain't you reached puberty?"

"Gee..."

"What you gonna do here?"

Eager reached under the table and dragged out a canvas grip. He opened it to show them that it was packed with great, purple boots. "I thought I'd catch up on my polishing."

They walked slowly down the wooden sidewalk, silent for the moment. "I wonder if there is something wrong with Eager?" Bill asked, but no one answered him. They were looking down the rutted street, at a brilliantly illuminated sign that cast a tempting ruddy glow.

SPACEMEN'S REST it said. CONTINUOUS STRIP SHOW and BEST DRINKS and better PRIVATE ROOMS FOR GUESTS AND THEIR FRIENDS. They walked faster. The front wall of the Spacemen's Rest was covered with shatter-proof glass cases filled with tri-di pix of the fully dressed (bangle and double stars) entertainers, and farther in with pix of them nude (debangled with fallen stars). Bill stayed the quick sound of panting by pointing to a small sign almost lost among the tumescent wealth of mammaries.

OFFICERS ONLY it read.

"Move along," an MP grated and poked at them with his electronic nightstick. They shuffled on.

The next establishment admitted men of all classes, but the cover charge was 77 credits, more than they all had between them. After that the OFFICERS ONLY began again until the pavement ended and all the lights were behind them.

"What's that?" Ugly asked at the sound of murmured voices from a nearby darkened street, and peering closely they saw a line of troopers that stretched out of sight around a distant corner.

"What's this?" he asked the last man in the line.

"Lower ranks cathouse. And don't try to buck the line, bowb. On the back, on the back."

They joined up instantly and Bill ended up last, but not for long. They shuffled forward slowly and other troopers appeared and queued up behind him. The night was cool and he took many life-preserving slugs from his bottle. There was little conversation and what there was died as the red-lit portal loomed ever closer. It opened and closed at regular intervals and one by one Bill's buddies slipped in. Then it was his turn and the door started to open and he started to step forward and the sirens started to scream and a large MP with a great fat belly jumped between Bill and the door.

"Emergency recall. Back to the base you men!" it barked. Bill howled a strangled groan of frustration and leaped forward, but a light tap with the electronic nightstick sent him reeling back with the others. He was carried along, half stunned, with the shuffling wave of bodies while the sirens moaned and the artificial northern lights in the sky spelled out TO ARMS!!!! in letters of flame each a hundred miles long. Someone put his hand out, holding Bill up as he started to slide under the trampling purple boots. It was his old buddy, Ugly, carrying a satiated smirk and he hated him and tried to hit him. But before he could raise his fist they were swept into a monorail car, hurled through the night and disgorged back in Camp Leon Trotsky. He forgot his anger when the gnarled claws of Deathwish Drang dragged him from the crowd.

"Pack your bags," he rasped, "you're shipping out."

"They can't do that to us - we haven't finished our training."

"They can do whatever they want, and they usually do. A glorious space battle has just been fought to its victorious conclusion and there are over four million casualties, give or take a hundred thousand. Replacements are needed, which is you. Prepare to board the transports immediately if not sooner."

"We can't - we have no space gear! The supply room..."

"All of the supply personnel have already been shipped out."