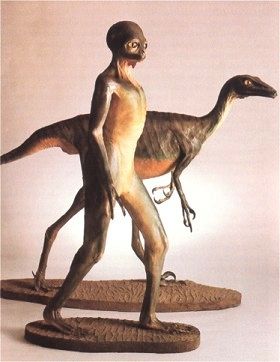

Where Do You Get Your Ideas From?PT: What originally sparked off the idea for West of Eden? HH: For a change, I can pinpoint the idea for the book... I was watching a television show about dinosaurs, and they had a guy from Canada, an anthropologist, who had made a model of what an intelligent dinosaur would look like, with big eyes...

Later on, when I showed it to Jack Cohen, he said it was completely wrong in every way! But it inspired me to think about intelligent dinosaurs: What if there were intelligent dinosaurs? What if mankind overlapped with intelligent dinosaurs and both existed in the same world? Click! That was the idea. I found that I had books on my shelves about intelligent dinosaurs, the facts had been there in the literature all the time, but no one had ever written any fiction about it. When I got started on it - just for a change, I had money in the bank - I thought: this is a big idea, I don't want to just throw it away on a single book. I wanted to take some time and establish a real physical world for the dinosaurs.

The ResearchHH: It's something I'd done in the past in small ways: I always research my books very carefully if there is something that can be researched. In Planet of the Damned I had the idea of mutual symbiosis, so I got an up-to-date book on symbiosis. And at other times later on I got a resource person to help me: in Stonehenge it was Leon Stover, and I did Skyfall with Gerry Webb, a high altitude physicist and science fiction fan. You can find a science fiction fan who knows anything, right up to professors teaching professorial courses - you get good solid material from someone who works in the field that you can't get out of a book.In doing West of Eden I had the time, the energy and the money over a couple of years, so that instead of creating the world myself I'd go to friends, people I knew who were SF readers and professors of their own departments, to generate the world, and then I'd write about the world picture. I contacted Tom Shippey, who is a linguist, and also a medievalist and historian; Jack Cohen, a biologist; Leon Stover, anthropologist and sinologist; and John R. Pierce from Bell Labs, who was a fan and an old friend. What I did, I tried to get a world picture - mostly with John R. Pierce: he had the idea in a story in Astounding of a flying ship that had flapping wings, and when they went inside this machine there was no bird there, just a big muscle attached to biologically built wings. This gave me the clue to have a biological science - I wanted to make the Yilane alien, but as alien as that may be, everything exists in the biology of the saurians. In the beginning I spent a lot of time with John R. Pierce; he's an engineer and physicist, he worked on the travelling wave guide, and he worked on radar during the war. He wrote science fiction under the name J.J. Coupling back in the thirties. He's a very nice guy - we talked about the background. Then I talked to Leon Stover about the hunter-gatherers, what their culture was like. So I picked up clues here and there. We had about a year's work, and about 30,000 words of notes before I thought about the plot at all. I had this vision of the world created, and then I turned it around a hundred-and-eighty degrees and started plotting the book. I've done that before with Leon Stover on Stonehenge: before we wrote the novel, we tried to decide who was living in Stonehenge at that time, attempted to get a world picture, and after having the world picture and inhabitants as best we could, we said "Well, why would they build Stonehenge?" PT: Didn't you also work with a philosopher, Robert Myers? HH: He was the last one. I was into the second book, and I realised I needed a philosophy for the Daughters of Life, and I was cooking it up, and I thought: What am I doing? I'd been employing people for everything else... so I looked in my list of academics from the SFRA (Science Fiction Research Association), and there they all were, Eng. Lit., Eng. Lit., Eng. Lit., and one physicist, and then Bob Myers, Professor of Philosophy. I wrote to him - he also teaches a science fiction course - he was very interested, so I flew down there with Joan on my way to California or somewhere. This little town had this Bible college which looks like Glasgow City Hall, same architecture, and I looked at it and thought: Where am I? He was happy to do it, you know. It sounded so realistic - instead of doing it myself, I let him do it. So that was the last outside aid I had. PT: When you've got all this research together, do you then have to put it out of your mind and come up with a story? HH: Not really. I put it in my mind, basically, and try and live in this world... One of the first - I mean... biologically based - things that we know - like frogs. Male frogs carry eggs on their backs. One species carries the eggs in its mouth, it doesn't eat for a couple of months until the eggs are hatched. So I thought, if they do that, they have a torpid state - that means the males are inferior and the females have to be dominant. I was braced about this by the fem libbers: You made the women the villains. No, if I could come up with something that was the opposite of human, I did it. A science that was biological instead of physical - and I didn't have any problem with that until one night I had to call Jack up at home: "Jack, could you do your biology without a centrifuge?" No, he said. Oh, Christ! I said: Is there any other way of separating things out? What about fraction columns? He said: Yes, but it's very slow. I said: I don't care how slow it is! Because you can't have a living creature spinning like a centrifuge! But you can have fraction columns as a way of separating out various things. So when a problem came up, I'd always go back to these guys. Two warring factions on one world, completely separate from each other in every way, and I tied them together with the boy, Kerrick, who spans the two of them. I was accused later of stealing from all these books about Natty Bumppo and things - a child captured by the savages in America. Nah, I'd never even read one of those things. It just worked out logically, I needed a bridge . I was necessary - I had to have them communicate somehow. PT: When you do that amount of research beforehand, how do you stop it overwhelming the story? HH: It's like writing a historical novel, like I am now. In Victorian days you have all the Victorian stuff you've learned about that you can draw upon - you draw upon the piece you need only. Leave stuff out, never jam it in - but give the feeling to the reader that you know all about it. And if you do know all about it, then the reader has that sensation. But having all that material - a three-dimensional world, physical and intellectual and biological - you can pull pieces out as and when necessary. And also those pieces help you develop the plot.

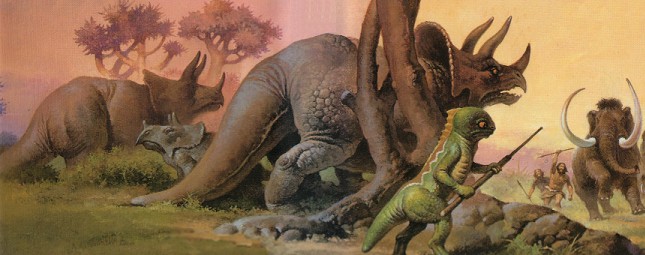

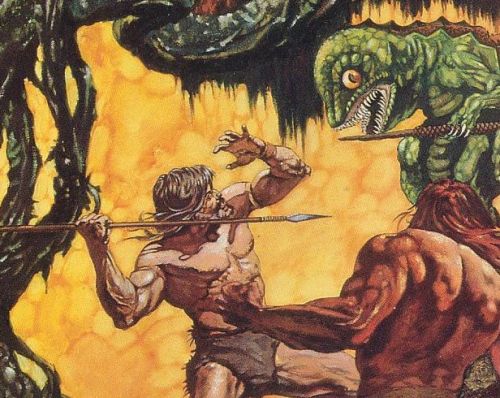

The ArtistsPT: Also on the team for West of Eden were two artists: Gino d'Achille, who did the cover paintings, and Bill Sanderson who did the interior illustrations...

|

|

HH: Gino d'Achille is an Italian artist living in London. I met him when he was doing covers for Granada as it was at the time. He was a very nice guy, and I decided I wanted to use him, so I went and met with him and gave him a lot of sketches and stuff.

We did a signing at Forbidden Planet and for the first time in his life he was signing books. As an artist he did his stuff in a vacuum and it was gone. Unlike writers, particularly science fiction writers. He was very chuffed - people asking for his autograph, talking about how they enjoyed his work. He did all three volumes. PT: In the first book, the endpapers have an illustration by Bill Sanderson of a map, drawn in the form of scales... HH: The map covers the area of the first book. The second book has a different map. In the book I very carefully didn't describe where these places were, because I knew the endpaper would be there for the reader to look at, and they'd realise when they looked at it closely that it was Africa and North America. Except the American edition left it out, so there was a certain amount of confusion there!

PT: You actually describe the scale-map in the second book... HH: Yes, deliberately so. Bill designed the map, and I liked it so much I described it in the second book. I bought a globe and photographed it to try and get different projections for the map. The city was the most important thing for them, so they wouldn't have a Mercatory projection or a Pole projection, they'd have city projections; in other words, the centre of their map would have to be their city, and the perspective as you move away is getting smaller and smaller. I gave the idea to Bill as a sketch, and it was his idea to put the scales on it. It was a very good idea, so I wrote it into the book, but it was his invention.

Marketing the BestsellerPT: When West of Eden was first published in the States, it was marketed like a mainstream 'bestseller' - how did that come about?HH: Every once in a while in life, serendipity works. Usually it doesn't work. Anthony Cheetham used to publish 'blockbusters' - he'd outline the book, find an author and give him some money to write it, and then he would sell it: he was a great salesman. I wrote a book for him called The QEII is Missing, and the firm went bankrupt two days before it was published. That takes care of serendipity. Reverse serendipity. But with West of Eden it was positive. I was working for Bantam at the time, they'd done a few of my novels. I went to see the editor there with the outline of the book, and what I didn't know was that Lou Aronica was thinking of doing a science fiction line within Bantam. He started an entire line called Spectra Books. West of Eden was chosen to launch the whole line. We had a meeting with the sales managers, and there was a big launch party, and a $60,000 advertising campaign. It worked so well they added another $30,000 to it - as opposed to British publishers who say [fake British accent]: Oh, it's going very well, let's take some of the money away! The woman in charge of publicity, I forget her name, she was a very good publicist, took me to lunch and said: I've never pushed a science fiction novel before, how do you do it? And I said I'd be happy to tell her. I told her about Locus, I told her about conventions, I told her about book review columns for science fiction, and she took notes. She sent me on an author tour across the United States: radio, television, newspapers, right across the United States from New York to California, ending up in San Francisco, which is the second largest bookselling city after New York. They booked a very posh restaurant and invited the managers from the bookshops, who knew me from science fiction. They liked the publicity material they got, and I signed books for their kids, you know. And next week the top-selling book in San Francisco was West of Eden because they put it out front. It managed to move 41,000 copies in hardcover, which is very good. Up until that time to get eight or nine thousand was tremendous in science fiction; you usually got two or three thousand. They were very, very pleased by it, put it out in paperback and kept it in print for about ten years. The series sold one and a half million copies, about 500,000 for each book. It launched their line, and they were happy with me. It earned out very quickly - I forget what the advance was, it wasn't very much, and it earned out in hardback, so I got income on it then.

|

|

PT: Before West of Eden was published, they got a lot

of quotes from writers to use in the publicity material... HH: It was the first science fiction novel ever marketed as a mainstream book. What I did was have them send out page proofs to every science fiction writer I could think of who owed me a favour, or who didn't owe me a favour but might enjoy the book. I wrote a letter to each of them to ask for some cover copy. That's how we got those lovely advance quotes. I get asked all the time to do cover copy. It's hard to do for a friend's book, I hate it. For years when I did the Year's Best I said I couldn't do it as I'd compromise myself...!

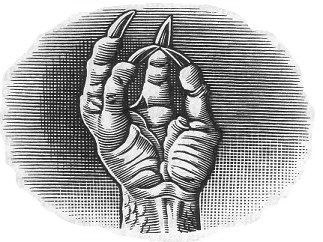

The YilanePT: Yilane culture turned out to be incredibly complex, with a language that develops with age and rank, from simple colour flashes from their palms, up to...HH: That was Tom Shippey's idea. He said there was no reason why we had to have a verbal language, we could have sign language, and a blend of the two might pretty much be in order. It was horribly complex, but then all of the book was complex, so why not? All the time, at the back of my head, I was saying everything had to be the opposite of humans, or the closest I could get to the opposite without being illogical. That way you get an alien that is completely alien to human life, but that is not alien to Earth. It is an Earth life form, not from some crap ancient planet, you know? PT: How do you take that and then make characters out of them?

And once you carry through the relationships with the physical things there, which science fiction always does anyway with back-plotting... A general novel is a novel of manners and personality, whereas in science fiction you have a set plot-line and you make people that will fit in that plot-line. They can be very human people, like Brian Aldiss does, but they still fit the plot, which is a science plot. The craft of science fiction is inventing all this nonsense, the art is disguising the fact that you know it! PT: What was your main intention in creating the Yilane? HH: I had the physics of their world, and how they physically looked. I had the sexual orientation, with the females on top and the males carrying eggs. I had a biological science, no physics all biology. A fear of fire because it was alien to them. And I set up the society, and then I turned it around and said: How would it work? If it's a matriarchy, what would be their relationship? They don't have any printed records, they only have word of mouth. Everything came out really from the society. And the character relationships. And the relationship to human beings. And it was pretty grim stuff. I remember one fan wrote to me and said: Harry, you're a very humorous writer, but there's nothing funny in this book...

Humour in Eden PT: There isn't much humour in the first book...

PT: There isn't much humour in the first book...HH: There's nothing funny happening in the first book! PT: There's more humour in the second book... HH: That's right. Also it's one third of the whole: once a book gets going I can relax a little - the world is established. PT: The old scientist is quite a fun character. HH: I saw the chance of having a humorous Yilane, especially with the Daughters of Life who were so deadly serious... PT: They're the nuns. HH: They're the nuns, so I thought we've got to have a funny priest in there, or a slightly humorous alien in one of the scientists. The only way of doing it was with her self-assurance, she loves the sound of her own voice, she's so sure of herself in every way. So no one's laughing in there, but we're laughing on the outside. But the head Daughter of Life gets her number after a while and gets on to her... gives her feed-lines. PT: Those two characters play well off each other. HH: That was fun to do. So I had a few jokes in that, and a few about the Tanu, because they are human after all. PT: And the hairy Paramutan - they're just sex mad! HH: (Laughs) Yeah, well they're somewhere between animals and Eskimos - it's a different morality up in the North! The Paramutan aren't Eskimos, they have their own over-sexed morality: they just enjoy the long winter evenings! I could bring a little bit of lightness there. But it was a grim society. You have the ragged-ass hunter-gatherers who are being forced south by the oncoming Ice Age, and they meet these horrible aliens who want to eat them and shoot them and kill them, and they hate them on sight. Jack Cohen, the biologist, had a terrarium in the middle of his house with snakes and lizards and all kinds of things. He had this gecko and held a handkerchief in front of it and snap, snap, snap it'd bite pieces out of it. A horrible-looking thing, but I looked at it and thought yeah, yeah, yeah. And he said: Aren't you afraid of them? I said: No. He said: You're one of the few people who isn't. Aren't you afraid of anything - spiders or snakes? I said no, I had absolutely no fear of snakes or spiders. But Tom Shippey was absolutely white, he couldn't go near these mothers! So when these two races meet, they have Tom's reaction. On seeing each other, they hate each other. That's their motivation, and the story gets moving out of the interrelation of the two. PT: You also have this thing where the Yilane have no concept of lying... HH: Yeah. It's the way their philosophy works. Why do we have to lie? It's an invention of mankind. The rigid cultural thing, with the order from the top down, and the lower orders are so dumb they can't do anything anyway... somewhere along the line it just seemed like a good idea: God knows where it came from!

Heroes and VillainsPT: The one thing I've never really figured out is whether or not the Yilane are villains...HH: In the Stainless Steel Rat books I tend to have really villainous creatures, mostly military. But in the straight novels I don't have any villains. Their way of life might be 'villainous' to the others' way of life, but I don't believe in villains particularly. And so here, from the human's point of view, they are really true villains, they're doing everything. And from the Yilane point of view, the human beings are foreign intruders in their world which they run completely. Once you get rid of the idea of villainy - I mean, you abandon villainy when you abandon the church and religion: the primal fall, basic evil, the devil... get rid of that and you don't really need villainy. You get warped, corrupt people - human beings or aliens - but not villains. No villains. In the Stainless Steel Rat you find villains, but they're black and white and the villains are stupid, but otherwise no. PT: The impression I got at the end of the trilogy was that the Yilane had lost, that their culture would be wiped out by mankind...

Genetically Engineered PigsPT: The whole idea of genetically warping living creatures for specific purposes, as the Yilane do, how much of that is based on what is possible?HH: All of it. Every bit of it is certainly possible, he said, opening today's Guardian which has a picture of two genetically bred pigs, bred to be phosphorescent... PT: Glow in the dark pigs, great idea! HH: We're doing all this stuff now, I wasn't really that far ahead. It was theoretically possible. I mean, look at the variety of life on Earth, which came about from natural causes. Or look at the dog, which has been around for maybe 20 or 30 thousand years? They were bred from wolves, yet compare the Chihuahua to a St. Bernard, and they're the same species. They can theoretically breed together; you can inseminate - because they couldn't do it physically! - with Chihuahua sperm and get a St. Chihuahua!

Fried SnakePT: Yilane society is based on no tools...HH: No physical tools. PT: ... and no fire. Could a complex society develop without these? HH: Why not? They don't need fire. Leon Stover said you couldn't have a society without fire, he was adamant, and we fought and fought and fought. Eventually it came down to the fact that everyone has these arguments, but they're countered by reality... he didn't want to do it, but it came down to one simple thing: I read an article, God knows where, about a snake, a boa constrictor, that broke the panel over a heating tube and wrapped himself around it, and fried himself! It had no pain sensation for fire, it was completely alien to them. PT: They lie out on a rock to absorb the warmth from the sun... HH: ... they love the heat, but they don't know that they can fry. And once I'd got that and their biological society, they don't need fire. And why not? It's extrapolation, which is what science fiction does, carry it through to its logical conclusion.

Returning to EdenPT: West of Eden took something like five years to write?HH: It was a year or two in the works before the actual writing, a year getting it all together, and then two years writing each book, a year-and-a-half perhaps, I don't work full-time. So it was written over a period of six or seven years. Having more time to think about it, I was seeing more complicated ideas and more complicated plots. In the old days all the novels were 60,000 words long: for the magazines it had to break into three 20,000 word parts. And when they started publishing paperbacks, six or eight signatures was 60,000 words. If you did 55,000 words, they'd have to use big typeface; if it was 70,000 words it wouldn't fit in! But then big books like Dune started being sold and publishers found they didn't have to adhere to that, so there was more freedom. Bigger books are more interesting to do. A lot of my books were thrown away on 60,000 words - I had to eliminate a lot of things to get a book into 60,000 words. And big ideas get big money, that's basically it! It took six years to do, two years for each book, hardback one year, paperback the next, third year the new hardback and a reissue of the paperback. That way they always kept copies coming out. Six years of my life, or seven or eight really with the two years to get it done. But it worked out, I was very happy with it. It sold well, and got a lot of very good reviews.

Interview conducted Saturday 12th October 2001, Dun Laoghaire, Ireland

|

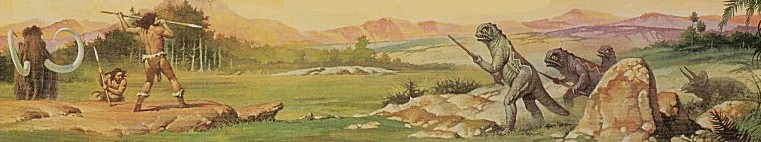

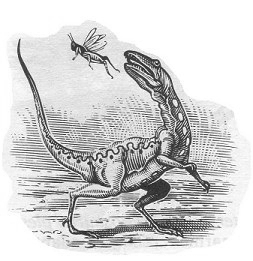

That's the one!

That's the one! Bill Sanderson was doing covers for New Scientist and I thought this

guy was really great. I wanted to get a style that was completely different

from anything else, and that scratch-board style seemed to fit it very

well. Bill was enthusiastic about it - he'd never read much

science fiction, but I gave him the idea for the book and did a lot of

rough sketches for him - and he modified and improved on them. And

he did all the drawings, and the endpapers.

Bill Sanderson was doing covers for New Scientist and I thought this

guy was really great. I wanted to get a style that was completely different

from anything else, and that scratch-board style seemed to fit it very

well. Bill was enthusiastic about it - he'd never read much

science fiction, but I gave him the idea for the book and did a lot of

rough sketches for him - and he modified and improved on them. And

he did all the drawings, and the endpapers. HH: Once you've go the culture going, and the interrelations

going, the characters come out of the interrelationships, always. And

they have very different interrelationships. All those schlubs at the

bottom would be treated like vermin, and what would be the relationship

to those on top? It's a top down relationship. And what's

the relationship between them and the males? And how do the males relate

to each other?

HH: Once you've go the culture going, and the interrelations

going, the characters come out of the interrelationships, always. And

they have very different interrelationships. All those schlubs at the

bottom would be treated like vermin, and what would be the relationship

to those on top? It's a top down relationship. And what's

the relationship between them and the males? And how do the males relate

to each other?