'Conspiracy' the 1987 World Science Fiction Convention. Friday 28th August 1987. Hewison Hall, Brighton Centre. 3pm. Recorded and transcribed by Paul Tomlinson.

Harry Harrison began by saying that "in many ways" John W. Campbell "invented modern science fiction, and the size of what he'd done is hardly ever appreciated". Campbell was a great and popular man because people got the greatest enjoyment out of his science fiction magazine, but today "...you can see how things have changed, because I had ten times the turn-out for [a talk on] Esperanto as I have for John Campbell, about which I am very unhappy..." The conference hall isn't even half full; there are older fans who were there and experienced the magic of Astounding for themselves, and younger fans who know of the legend of John W. Campbell, myself included, and maybe younger fans who didn't know of Campbell and had turned up to see Harry Harrison.

HH: I think the only reason I was asked to speak here today was that I grew

up in the Campbellian era - I knew John, and worked with him, and among

other things he asked me to edit the magazine after his death - but I said

'My God, but you're going to live forever!'

HH: I think the only reason I was asked to speak here today was that I grew

up in the Campbellian era - I knew John, and worked with him, and among

other things he asked me to edit the magazine after his death - but I said

'My God, but you're going to live forever!'

Going back, I was of the generation that grew up reading Campbell's magazine - reading all the magazines of course - but John was the one who shaped modern science fiction and got us all in this room today!

Before Campbell came along science fiction was a pulp thing, it came out of the pulps. In the good old days of pulp they used to publish 'six up.' They put six different covers a month, full colour [he draws a big printing plate in the air with six covers laid out)... I remember old Hugo Gernsback had an air war, a love, a western, a romance and he had a hole there. He'd been doing science fantasies in his science titles... SF was invented by accident and stayed alive by accident!

Campbell came along and threw out all the rotten writers... the good writers knew his name and looked for him... and there were new writers: Heinlein, Campbell, Doc Smith...

It was a private engine shunting along in New York in the back of a paper warehouse, and John was sitting there doing his magazine for nothing... a hundred dollars a week or something. And I read it and loved it, and that was life everlasting! I read them before the war, in the army, and I read them after the war. They used to come out on a Thursday - a Thursday late in the month - and I found a subway station down town, about a half-hour's ride - an hour's round trip - that had them one night early, and I read it on the way back.

And this thing was read in countries all over the world. Brian [Aldiss] and I have talked about this over a drink, and before the war - when Britain used to export things! - a big ship would come over [to America] full of china and brassware and what have you, and go back empty because the States had nothing to sell. They'd fill the ship with ballast, which was pulp magazines all roped together and used as ballast because they were free. And in England people would buy them from Woolies - that's 'Woolworths' for you Americans - and they'd have big bins full of 'Yank Mags' for tuppence or threepence... and Brian Aldiss was reading those things and getting the same charge [from them] over here. Campbell's magic worked.

After the War when I started writing I went to see John, and he was always an affable man... but he'd make you work very hard. He'd make your head spin... Poul Anderson always said that having a conversation with John was like throwing manhole covers at each other, but they were intellectual manhole covers.

An example of a John Campbell conversation consisted of a series of pointed

questions. One day he looked at me and said: 'You're a medieval peasant and

you're allergic to white bread, what happens? Speak up...' I said: 'Er...

er... I eat white bread and I get sick.' 'Right. And you fall down foaming

at the mouth. Where do you get white bread, huh?' 'From the lord?' 'No,

you're a peasant, you don't eat white bread.' 'Maybe he throws it out in

the garbage.' 'He wouldn't let the ordinary men eat it. You're a peasant,

now where do you get white bread and fall down foaming at the mouth?'

An example of a John Campbell conversation consisted of a series of pointed

questions. One day he looked at me and said: 'You're a medieval peasant and

you're allergic to white bread, what happens? Speak up...' I said: 'Er...

er... I eat white bread and I get sick.' 'Right. And you fall down foaming

at the mouth. Where do you get white bread, huh?' 'From the lord?' 'No,

you're a peasant, you don't eat white bread.' 'Maybe he throws it out in

the garbage.' 'He wouldn't let the ordinary men eat it. You're a peasant,

now where do you get white bread and fall down foaming at the mouth?'

And I had about half-an-hour of this. My palms were clammy... I was wishing for salvation... lightning to strike or something... Finally, reluctantly, he sits down heavily and says: 'The only place you get white bread is in church when you eat your Host and that explains medieval possession. Go away and write a story about it.' 'That's a whole story?' 'You can find a way of writing it.'

But I never did! So that's a Campbell story, if you want to write it and send it in to Analog... they'll buy it. Tell them John gave you the idea!

That was one of the things about John, he was very free with his ideas... and one person, who I shall not mention, made his living just by rewriting John Campbell ideas.

You must remember that John was a big man in every way - he trained an entire generation to read and write. And he beat everyone into line. We had him out to Chicago to one of the colleges, and talking to the Professors had him jumping up and down when they said 'I understand that science fiction has only a limited scope compared to English Letters'. 'Science fiction begins with the Big Bang and ends with the heat death of the universe - English Letters is here between my fingers!'

And you find the same wild enthusiasm in his stories, which still hold up pretty well, if you read them. After a while he stopped writing, he always said: 'If I have a thousand writers, I write a thousand stories a year!

But he read and read and read. And he really believed, and believed strongly in editorial input. I spent endless amounts of time with John and he was special, he would expand the mind. The novels I wrote for Astounding / Analog, four or five of them, were really collaborations with Campbell. Take Deathworld. I did a page-and-a-half outline and I thought it'd make a novel. I'd sold him one short story, the Stainless Steel Rat [short] story, and I didn't know how to go about selling a novel, I had no agent. He sent back a seventeen page letter saying how I might expand the idea. He never asked you anything, he just showed you where your idea might go. He sent all this material, and I thought 'Gee, that's a great idea!' So like I said, you could make a living just writing his ideas, he'd buy 'em. It was easier to sell him a novel because you'd take it to him and work it out two or three times, expand it. Short stories he'd just buy - he'd show you what was wrong with it.

Isaac [Asimov] always said The Three Laws of Robotics were given to him by John W. Campbell... he says it in public, make sure you know that.

But many times you'd fight him tooth and nail...

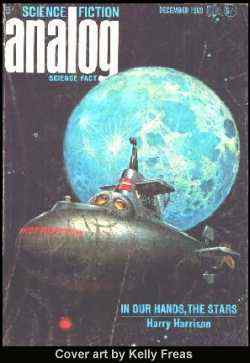

I did one book called One Step From Earth *

which was about an

imaginary machine such that a spaceship accelerates at one gee for as long

as you like, then decelerates at one gee. He'd done an editorial on this,

and I kept thinking about it, and years later when I wrote the book (about

ten years after I'd read the editorial) I went and had the figures run up

on a big computer to see how long, at one gee continuous acceleration, and

one gee deceleration so you have zero at both ends, it would take... five

and a half hours to the moon. And the best part would be three or four days

to the moon. And John had worked it out on his slide rule, and the big Cray

came up with John's figures.

I did one book called One Step From Earth *

which was about an

imaginary machine such that a spaceship accelerates at one gee for as long

as you like, then decelerates at one gee. He'd done an editorial on this,

and I kept thinking about it, and years later when I wrote the book (about

ten years after I'd read the editorial) I went and had the figures run up

on a big computer to see how long, at one gee continuous acceleration, and

one gee deceleration so you have zero at both ends, it would take... five

and a half hours to the moon. And the best part would be three or four days

to the moon. And John had worked it out on his slide rule, and the big Cray

came up with John's figures.

(In the title story) I had one of the characters looking out at the view and giving a lecture about my point of view... not just about politics, about evil... and I'd sat down and typed two or three pages of conversation, the readers had enjoyed themselves a bit and now I'd give them the propaganda... and John wrote back saying: 'You're being unfair here, Harry, because the other guy isn't replying. He shouldn't say 'Oh, I understand', he should say...' And John had written about a page-and-a-half of counter-propaganda; and I looked at it and said: 'Well, it's his magazine. And I want to sell it... I put it in... had John's words coming out of the other guy's mouth.

But when the book edition came out I threw it away! It was my book! One of the small victories you can have.

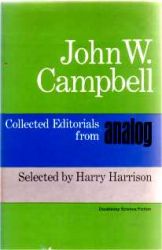

When I came back to New York - I was living in Denmark - he said 'I've got a great idea for a collection, Harry.' I said: 'What?' He said; 'A collection of my editorials.'

You remember that in Analog / Astounding he had his very 'eclectic' - his word - editorials in every issue... absolute madness sometimes! Very argumentative, profound... and he said this and I stood with eyes wide open and said: 'That's an idea.' And he said: 'I want you to edit it, and I said: 'Great! That's an idea!'

So I edited this thing, went through thirty or forty years of Astounding

/ Analog, and I found the really good ones, and I put it all together,

and he said: 'Very good, Harry, but I suggest you put in the mobsters.' I

said: 'I don't think we should, that really doesn't do you justice'... this

was an editorial which stated very simply that any riot - anywhere in the

world, Calcutta, Belfast, London, New York - was controlled by the

Communists in Moscow. The concept was... absolute nonsense. But 'No,' he

said. 'It was absolutely true'. And I worked very hard, and we spent about

a year at this and I said: 'Look, I'm very sorry John, if you want to put

it in put it in, but take my name off. I will not be associated with the

thing.' And finally he said: 'Okay, you're the editor!' Two years I'd been

working on it!... You could never win, but you could fight him to a draw!

So I edited this thing, went through thirty or forty years of Astounding

/ Analog, and I found the really good ones, and I put it all together,

and he said: 'Very good, Harry, but I suggest you put in the mobsters.' I

said: 'I don't think we should, that really doesn't do you justice'... this

was an editorial which stated very simply that any riot - anywhere in the

world, Calcutta, Belfast, London, New York - was controlled by the

Communists in Moscow. The concept was... absolute nonsense. But 'No,' he

said. 'It was absolutely true'. And I worked very hard, and we spent about

a year at this and I said: 'Look, I'm very sorry John, if you want to put

it in put it in, but take my name off. I will not be associated with the

thing.' And finally he said: 'Okay, you're the editor!' Two years I'd been

working on it!... You could never win, but you could fight him to a draw!

His politics, I won't say they were right or wrong - they never caused me any problems. Well, maybe verbal problems, but never publishing problems. I recall one day in his office, G. Harry Stine was there (he writes under the name Lee Correy... juveniles... )... some moron in South Virginia Had produced research that proved that the negro mentality was less than the white mentality... smaller brain-case and whatever. And they had a curve - a bell-shaped curve of intelligence... with the whities up here and the darkies down there or something... and I said: 'No, no.' They said: 'But it's proved in West Virginia.' and I said you could prove anything in West Virginia, there's no problem with that!.. And G. Harry was nodding his head, and finally in desperation I shouted: 'Gentlemen, you can't reduce everything in life to a bell-shaped curve.' And they both said: 'YES YOU CAN!'

That was the thing with Campbellian theory, everything was analysable that way... but he did not force his writers to work that way. I'd sell him stories which he'd argue with greatly, and then he'd print them.

Other people fought with him tooth and nail to sell him a story from a different field that had nothing to do with anything he liked - but he'd buy it if it was a decent story.

Horace Gold would rewrite every single line of every story... Isaac Asimov's first novel [Pebble in the Sky]... written into the plot, set a million years in the future, something had to be found... besides the regular plot... and they open this box and it's the U.S. constitution. It was written by the editor... it had nothing to do with the plot, but Isaac wanted some money - these were the days when science fiction was a hobby for the writer... no one earned money at it.

Ted Sturgeon had a very different story called 'Killdozer' and it ran about 12,000 words and John only wanted 5,000 word stories, so he [Sturgeon] sold it to John putting 5,000 words on it and only got the $50 or $100 and the book was set in galleys and there were these big galleys ganging out... it was 10,000 words too long! Imagine lying about the length of 'Killdozer' to sell it! There really were giants in the world in those days!

I'm waiting for the giants to appear today. It's so easy... anybody who can write a barely competent, barely literate science fiction novel (most of them aren't literate, but I won't mention any names... like H*** or anything) will sell it!... And get three, four, five hundred grand for it.

I started out reading a lot of this stuff... I don't read much anymore. If someone recommends a book I'll read it... but the biggest question I have from fans is 'What shall I read?'

One of the biggest questions I have is 'What shall I read?' Here's a field... ten percent of all American fiction is now science fiction... The writers around today are a bunch of bums and hacks... I mean, there are over 600 science fiction writers in America, and I think five of them can write. There were over 800 original [sf] novels published last year... I think three are readable! One of mine and two of somebody else's!

[This prompted a question from the audience: If Campbell was still alive today whose work, apart from your own, would he be buying?]

HH: Brin, perhaps. Bear... and there are maybe twenty other writers around who he'd have pulled in and kicked up the kilt and taught to write. He had a very keen eye...not for prose, but construction of story.

After the war there was a brief period when John created modern science fiction; Horace Gold developed it, moved it into other directions with the non-hard sciences; Tony Boucher, with F&SF, caught in other writings with the fantasy sort of thing - it's hard to articulate an emotional attitude, I mean we all read the stuff... and I see a few familiar faces here, the older readers had the same feeling, didn't you? You remember those golden days when Astounding came in? Wow! It was life everlasting; and we got Modern Stories too, and Fantastic Mysteries - -I always bought that second-hand, it wasn't very good! And Thrilling Wonder stories... and there was a lot of rubbish around... We only really got jazzed up on John.

If you look back at the anthologies from the fifties, and forties... Brian and I did 'Decades' - we decided to do a series of every ten year period and do a history of science fiction; so we started with the forties which were the golden years of science fiction and we did the anthology; and we did the fifties and sixties... this was back in the early seventies... and they said 'What are you going to do now?'. So we went back to the thirties, and that killed off the series! Most of it was dreck! I used to mourn that the old pulps are crumbling to dust, now I'm happy that they're crumbling to dust, they just worked in their day.

But we were just looking for good stories, and in the decade of the

forties, every story was from Astounding... out of all those

magazines, and during that period there were forty or more... and we didn't

do it on purpose, it was just that all the writing in the field was going

on there.

But we were just looking for good stories, and in the decade of the

forties, every story was from Astounding... out of all those

magazines, and during that period there were forty or more... and we didn't

do it on purpose, it was just that all the writing in the field was going

on there.

All the first novels published in paperback - remember the first paperback wasn't published until the fifties - all the first novels were all serials from Analog, and they were all the same length...you couldn't sell longer than sixty to seventy thousand words - occasionally longer... the field was his, the writers were his and we owe an awful lot to him.

I'm just talking ancient history here... I could sum this whole talk up in one sentence: John Campbell invented modern science fiction. If you're historically minded, that's very important. I wish writers were more historically minded and took a look at that stuff and tried to get their fingers out of their... noses, and get some of the life back. The stories they published had life!

George [Hay] here came up with one of the best ideas in the world: to put a statue of H.G. Wells on Primrose Hill, where the Martians landed. I wish we could do that. But I also wish we could put up one to John Campbell who is equally deserving.

I'd like to find a place for a Campbell memorial... Years ago when Campbell died, I went down to New Jersey [to the funeral], and Isaac [Asimov] was driving a car and Lester [del Rey] was with him, everyone was there. And I said: 'Where's John?' They said: 'He's not here', and I said: 'I know he's not here!... but he didn't want a funeral at all, he was cremated I think, scattered somewhere, she [Mrs. Campbell] wouldn't say a word...and we all met at the funeral home and there was no body there, a good Campbellian funeral! Isaac read something from the Old Testament; George Smith read something, and I read from one of his editorials...one of the nasty ones, you know! And we went back to the house and had some food and made some jokes, and we knew John was just going by up there [looks up as if there's a ghost on a balcony] enjoying the whole thing. And Jimmy Gunn said we should have some kind of memorial for him... and it kind of stuck in my mind... and a few years later, the Hugo had been bought and sold one more time... and we were so pissed off at the award for best novel of the year that we founded the John W. Campbell Memorial Award for the best novel of the year. We've got a jury of five or six or seven academics who are also fans - we figured their choice could be no worse than the bought choice of the fans and the writers... but I really did want to do a memorial in some way...

[At this point, someone in the audience decided it was time to introduce a

little of Astounding / Analog's history into the discussion, by pointing

out that what John Campbell did he did by building on the foundations of

the magazine's previous editor F. Orlin Tremaine, then went on to say that

Campbell transformed the whole magazine field and got very little reward

for it. The speaker said that he had spoken to Mrs. Campbell "and she

revealed to me something which very few people seem to know: that his

estate never received a godamned cent from Condé Nast [the then

publisher] which shows what happens when you give good and faithful

service."]

[At this point, someone in the audience decided it was time to introduce a

little of Astounding / Analog's history into the discussion, by pointing

out that what John Campbell did he did by building on the foundations of

the magazine's previous editor F. Orlin Tremaine, then went on to say that

Campbell transformed the whole magazine field and got very little reward

for it. The speaker said that he had spoken to Mrs. Campbell "and she

revealed to me something which very few people seem to know: that his

estate never received a godamned cent from Condé Nast [the then

publisher] which shows what happens when you give good and faithful

service."]

HH: Tremaine did a good magazine, much better than the other stuff around it... and Campbell came out of Tremaine, he was already writing the stuff then...Then Street and Smith were sold to Condé Nast, and Condé Nast were sold to Davies... and they had one Catholic... not weirdo... immaculate virgin, and the total salary was maybe forty-five hundred a week or something, and it made profit of ten, twenty, thirty thousand dollars. Then all the pulp magazines were scrapped, all the girlie magazines were scrapped, Sports Illustrated was scrapped... but through all of this going on in the publishing house, Astounding kept rolling along... John didn't ask for anything; he got very little salary - enough to stay alive - and did his magazine. And many times he'd say 'I'm going to live forever! and he did... he was eighty-one when he died, but he was watching The FBI in Peace and War, and he went over and had a stroke, and that was the end of poor old John... but he created this world...

[A question which seemed bound to raise its head was finally asked: Campbell was such a hard-headed commonsensical man when it came to the science fiction he bought, how come he fell for things like Dianetics and the Dean Drive?]

HH: He was a physicist, he went to M.I.T... he was a very hard-headed man, but he had a very open in-put. I never knew whether he believed in this nonsense... With Dianeties, he believed in it, I think we all believed in it when it came along, and by the time opinion changed he'd moved on to something else. I remember when Dianetics first appeared, it appeared as an article [in the May 1950 issue of ASF] and there was a very fine review of the book or the article by Jim Blish, about three months later there were some very nasty letters destroying Jim Blish's arguments completely... they were written by Jim Blish! He'd read the book again and said: 'That's absolute nonsense!' John's brother-in-law, Joe Winter MD, believed it all and he picked up an outboard engine and died of a heart attack. Beliefs kill you, you all know that.

People came up with these mad ideas and he would print them, and he kept

them going around in circles. The Dean Drive: Dean was an airline pilot who

took a power drill and attached these fourteen balls and put it on a scale

and photographed the scale which said, I don't know, twelve pounds, turned

it on and it weighed only eleven and a quarter pounds - three-quarters of a

pound less. And the theory was right! And there was correspondence going on

- 'It violates the law of conservation of energy' - which of course it

does!... and John R. Pierce, an engineer, head of Bell Telephone

Laboratories for a long time, and a good science fiction writer... a

physicist, John couldn't face this. He knew conservation of energy was

conservation of energy. So what John did, being a good researcher, he went

out and bought a scale with the same name on it, which was a spring scale

and not a balance scale, and did the whole bit with the damned Dean Drive

and set it working and found that it didn't decrease the weight of it - the

vibration of this rotten apparatus caught the moment of vibration of the

spring and affected the reading! If John Pierce hadn't done this...

People came up with these mad ideas and he would print them, and he kept

them going around in circles. The Dean Drive: Dean was an airline pilot who

took a power drill and attached these fourteen balls and put it on a scale

and photographed the scale which said, I don't know, twelve pounds, turned

it on and it weighed only eleven and a quarter pounds - three-quarters of a

pound less. And the theory was right! And there was correspondence going on

- 'It violates the law of conservation of energy' - which of course it

does!... and John R. Pierce, an engineer, head of Bell Telephone

Laboratories for a long time, and a good science fiction writer... a

physicist, John couldn't face this. He knew conservation of energy was

conservation of energy. So what John did, being a good researcher, he went

out and bought a scale with the same name on it, which was a spring scale

and not a balance scale, and did the whole bit with the damned Dean Drive

and set it working and found that it didn't decrease the weight of it - the

vibration of this rotten apparatus caught the moment of vibration of the

spring and affected the reading! If John Pierce hadn't done this...

But it was busy then, things were happening... you didn't have to build a machine, you just had to draw a wiring diagram that worked... He did dowsing, dowsing went on for a long time... we don't believe, but we all want to believe or disbelieve... your mind was being tickled, a little wire in there was shaking things up.

I think he was a receptacle for ideas. He'd get an important new idea, he'd let it bubble around there, he'd drain it down to his subconscious, then held skim it off as no good. But by then, when everyone was having doubts, he'd gone on to a new idea... he went in another direction.

[This prompted the following from a member of the audience: 'In relation to what Campbell may or may not have fallen for, two items in the newspaper or on the radio in the last two days: One, Geller has gotten loose again! And in the Daily Telegraph about three days back, someone is being funded to study applications of gyroscopes which 'appear not to obey Newton's Third law' - so people are still being conned! It's still happening!]

HH: I know it's happening. We have the Rousseau Organisation in the States, Isaac Asimov belongs to it, I belong to it, the Great Rhandi belongs to it, who write letters and protests and say bring your proof forward. I have a standard agreement with the New Scientist that whenever one of these books comes in purporting to be fact, they send it to me and I put the boot in!

I did one a little while ago on a variation of flatland you may have seen,

and the guy said he'd been to flatland and all that... And you always seem

to find a place where these books turn and they put in a bit of fiction.

And he did... and he put in a lot of facts, they always put in a lot of

real facts... like there was a German went to Australia in 1890 who kicked

down anthills - which is what Germans did in Australia in 1890! - held kick

down an anthill and the ants would rebuild it, the image of what it was

before. And then he kicked down the anthill and drove a steel sheet through

it, and the ants rebuilt it and they pulled the steel sheet out and all the

arches met, which proves the group mind of the ants... but it doesn't prove

or disprove just because the things still met! I questioned it and queried

it, and I mentioned it to Marvin Minsky about six months later - and

Marvin, as you know, is a good science fiction fan and he's one of the guys

who invented artificial intelligence, he teaches at M.I.T - he really knows

what he's doing, and he loves science fiction, the man can't be all bad!

He'd read a bit about some research and the arches ants build are a

formation of the mathematical structure of their saliva consistency and the

shape of the sand. If you get ant spit and sand, they build arches of that

shape all the time!

I did one a little while ago on a variation of flatland you may have seen,

and the guy said he'd been to flatland and all that... And you always seem

to find a place where these books turn and they put in a bit of fiction.

And he did... and he put in a lot of facts, they always put in a lot of

real facts... like there was a German went to Australia in 1890 who kicked

down anthills - which is what Germans did in Australia in 1890! - held kick

down an anthill and the ants would rebuild it, the image of what it was

before. And then he kicked down the anthill and drove a steel sheet through

it, and the ants rebuilt it and they pulled the steel sheet out and all the

arches met, which proves the group mind of the ants... but it doesn't prove

or disprove just because the things still met! I questioned it and queried

it, and I mentioned it to Marvin Minsky about six months later - and

Marvin, as you know, is a good science fiction fan and he's one of the guys

who invented artificial intelligence, he teaches at M.I.T - he really knows

what he's doing, and he loves science fiction, the man can't be all bad!

He'd read a bit about some research and the arches ants build are a

formation of the mathematical structure of their saliva consistency and the

shape of the sand. If you get ant spit and sand, they build arches of that

shape all the time!

[A member of the audience cautioned us not to dismiss new ideas out of hand, pointing out the example of George Craven and his microwave theory who was disbelieved by academics, but proved right in practice... the speaker said that maybe Campbell meant for us to consider ideas, no matter how strange they might sound.]

HH: Also, if any of you have ever taught science, you'll know there's no experiment that's foolproof... that won't go wrong. Always! We know it should work, and the apparatus is absolutely clean - and it doesn't work. I think the best, certainly the most dramatic, one I saw was in science when I was eight or nine years old in school in the states, and we had an alcoholic science teacher... and she'd usually come in and give us a chapter to read and answer questions, and she'd have her 'cough medicine' in her bag! And she decided to show us that when metallic sodium is put into water, it bursts into flames. And all of you here who have done your stink know you get it under oil, and you take a dry knife and take a bit like a fingernail paring and put it in a basin of water and it goes SHOOF! Very, very dramatic...so she took this thing out and cut a piece about the size of a lozenge! And she dropped it in the water and it went WHHEEEENG!!! and burned all the hair off her face, turned her coal black! And a piece of sodium shot up and stuck in the plaster ceiling and smoked and burned like crazy! And we were impressed, I'll tell you! 'What are you going to do next week, Miss?' That was 'science' for me!.. For years until I left the school you could see a bit of black stuck in a hole in the ceiling...

[QUESTION: Would you say something about the factual parts of Astounding - in England they were cut .until the later Issues... ]

HH: The non-fiction parts were an essential part of my education and of other young readers'... apart from the nonsense we talked about, we had physicists getting in there, and geographers, ecologists... I think the first time I heard the word 'ecology' was in an article in Astounding. I was very interested and started buying a few books about it... He liked engineers and practical people... 'We need more stories on buying a new camera' or buying a new microscope... so he knew who he was aiming at. He was an educator, I think... he was a lot of things, but he educated his readers, dragged them kicking and screaming into intelligence... I know a lot of physicists and engineers who got into it because of Astounding.

I was in the US army and I was in Moreno, Texas and we had an old valve, or tube, radio, and we'd put it on the truck in the morning and play it, and then we'd have to push the truck back at night because we'd drained the battery in four hours. And we'd sit in this thing and shoot off guns... and the broadcaster came on and said: 'A bomb has been struck on Hiroshima... a bomb of a new type, reputed to have the power of 10,000 tons of dynamite' - 'Oh, I said, the atom bomb.' 'It's called the Atom Bomb.' The guys said 'Wha? How'd you know?' I said I read it in Astounding. It was all there... including in an early issue a spacehip powered by gasoline going pop-pop-pop-pop all the way to Mars! An internal combustion spaceship!.. He never pretended to be always right! Only Sam Moskowitz says science fiction predicts the future... it doesn't at all.

GEORGE HAY: Do you think it would be possible to publish today in a popular magazine some of the stories Campbell either commissioned or bought? I'm thinking... if you read the Campbell letters, some people just explode when they read these letters... because, you remember, one of Campbell's editorials - I think it's published in your collection - was on 'Rape as an evolutionary mechanism.' It's very strange but this sort of thing doesn't go down terribly well today... nowadays anyone who is a millimetre to the right of centre is described as a fascist. When you ask these people what a fascist actually is you get the oddest replies... the point is that Campbell liked to provoke people... first of all he was right wing himself, but apart from that he liked to provoke people...

HH: John was not right wing, he was not a fascist, he was a technocrat. He loved technocracy. If you want to know what technocracy is, read a Bob Heinlein story called "The Roads Must Roll." Basically the idea of technocracy arose in the states in the '30's during the depression, it was that all problems are solved by bellshaped curves. Engineers would rule the world and they would take care of us. And it's a different thing from fascism... on a scale of left to right you might call it right, but I call it technocracy.

GH: What worries me is that today, pardon me if I use this crude word, there's a sort of 'left wing' prejudice which makes it very difficult for anyone to ask open-ended questions.

HH: I beg your pardon?! Are you speaking from the British point of view? Or the world point of view? Or the American? I find that in Britain it's a Tory press, and if you read the Telegraph or the Mirror or the Times with anything with a headline which mentions the Labour party or hard-liners, it is a work of fiction. It's a Tory press in this country, so you can't say that the left in the eighties is controlling things.

GH: I take that back. On either side there is a reluctance to actually look at something as if you didn't know. One of the things Campbell... read these letters, Campbell is always saying one of the great advantages of the Mormon religion is that they do not claim that all truth is known. They say that for the future God is ignorant. We can admit that we don't know something. And today I find we live in a society where anyone who admits he doesn't know is out.

[From the audience: Just like Socrates... Socrates was a great master, and yet he said: My advantage is that I don't know, and you claim that you know. Now prove to me that you know. And nobody ever defeated him.]

HH: I'll tell you something: all the academics I know who are decent people, if you ever fluster them, they'll say 'I didn't know that.' Like Jack Cohen, now Jack knows everything about biology, I mean everything. And I mentioned something to him from a book about insect larvae life, and he said 'I never heard of that' and asked for the reference. People who know will say they don't know, people who don't know will know everything.

[QUESTION: Didn't Campbell himself make the point, many years ago, that it was impossible to do a proper study of the comparative intelligence of, for instance, blacks and whites in the United States then, and isn't it even more impossible to do the same now, because whatever conclusions a totally impartial amount of research would come to, somebody or other would misuse it or abuse it, or use it as evidence of prejudice or racism or what have you...]

HH: I'm sure he did say it. It sounds like something he would say...

HH: I'm sure he did say it. It sounds like something he would say...

I wish the world were a better place, that there were more editors like John Campbell - we miss him very much. I feel an extreme need for someone to buy me a drink to cheer me up, because science fiction as you know is dead. I think it's run it's course... I think we've institutionalised science fiction... millions of books are published every year, and they're getting crappier all the time... with a few exceptions, you know.

Thank you very much for listening to this.

* Webmaster's note:

The book is in fact called In Our Hands, the Stars. One Step From Earth is Harry's collection of Matter-Transmitter stories, the title story of which appeared in the the March 1970 issue of Analog, under the pseudonym Hank Depmsey.